Assessment of the preventive effect of knockdown of cellular genes NXF1, PRPS1PRPS1 and NAA10 in influenza infection in an in vitro model

- Authors: Pashkov E.A.1,2, Shikvin D.A.3, Pashkov G.A.1,2, Nagieva F.G.1, Bogdanova E.A.2, Bykov A.S.2, Pashkov E.P.2, Svitich O.A.1,2, Zverev V.V.1,2

-

Affiliations:

- Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University)

- I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

- Moscow State University of Fine Chemical Technologies

- Issue: Vol 70, No 1 (2025)

- Pages: 66-77

- Section: ORIGINAL RESEARCHES

- URL: https://virusjour.crie.ru/jour/article/view/16712

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.36233/0507-4088-289

- EDN: https://elibrary.ru/oqonmm

- ID: 16712

Cite item

Abstract

Introduction. Influenza is an acute respiratory viral infectious disease caused by the influenza viruses. Current preventive and therapeutic approaches are of great anti-epidemic importance, but there are a number of problems, such as the rapid emergence of resistant strains, the lack of cross-immunity and the effectiveness of vaccines. One of the approaches to the development of anti-influenza agents is the use of RNA interference and small interfering RNAs complementary to the mRNA target of viral and cellular genes.

Aim ‒ to evaluate the prophylactic anti-influenza effect of siRNAs directed to the cellular genes NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10 in an in vitro model.

Materials and methods. Antigenic variants of influenza A virus: A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/WSN/33 (H1N1) and A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1); cell cultures A549 and MDCK. The study was performed using molecular genetic (transfection, NC isolation, RT-PCR-RV) and virological (cell culture infection, titration by visual CPE, viral titer assessment using the Ramakrishnan method) methods.

Results. It was shown that siRNAs targeting the cellular genes NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10, when used prophylactically in cell culture at a concentration of 0.25 μg per well, during infection with influenza virus strains A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/WSN/33 (H1N1) and A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1) at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01, reduced viral replication to a level of 220 TCID50 per 1 ml of cell medium, whereas in control untreated cells the viral yield was ~106 TCID50 per 1 ml of medium.

Conclusions. Reproduction of influenza A viruses directly depends on the protein products of the NXF1, PRPS1, and NAA10 genes. Reduced expression of these genes disrupts the life cycle and activity of influenza viruses. Such an approach can potentially be studied and used for closely and distantly related representatives of other virus families.

Keywords

Full Text

Introduction

Influenza is an acute respiratory viral infectious disease induced by influenza viruses belonging to the Orthomyxoviridae family. According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA) information bulletin, a steady increase in the number of cases of influenza infection has been registered in the world from 2020 and up to the present time1. The annual increase in infections with influenza type A virus in the human population raises concerns about the possibility of a new pandemic of influenza [1].

The course of influenza varies from acute transient fever to severe illness, with complications that can cause dysfunction of the cardiovascular, respiratory, immune, genitourinary and central nervous systems, as well as secondary fungal or bacterial infections [2‒8]. Current prophylactic and therapeutic approaches are anti-epidemic measures of high importance, but there are also a number of problems, such as the rapid emergence of resistant strains, lack of cross-immunity and vaccine efficacy ranging from 70 to 90% in patients under 65 years of age and 30 to 40% in patients 65 years of age or older [9]. Along with this, the composition of influenza vaccines should be updated annually according to the predicted circulation of certain antigenic viral variants [10, 11].

To date, four drugs are recommended by the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, USA) for the therapy of influenza infection: Xofluza (Baloxavir marboxil), Rapivab (Peramivir), Relenza (Zanamivir) and Tamiflu (Oseltamivir), classified according to the mechanism that inhibits influenza reproduction [12, 13]. The mechanism of action of Xofluza is to inhibit viral RNA polymerase activity, while the others inhibit influenza virus neuraminidase [13]. The rise of emergent drug-resistant strains necessitates the development of innovative approaches to create new anti-influenza drugs with a pronounced antiviral effect, improved tolerability and reduced toxicity before the onset of the pandemic.

Summarizing the above, it can be emphasized that the development of cheap, effective and safe anti-influenza prophylaxis and therapy is of high relevance to ensure public safety.

RNA interference is an evolutionary mechanism of gene expression regulation and maintenance of immune homeostasis in eukaryotes. The regulation of gene expression in this case manifests itself as a temporary silencing of the activity of the target gene. The essence of RNA interference is to suppress the expression of a target mRNA or gene using a molecule of miRNA. The mechanism of RNA interference is that foreign exogenous dsRNA is cleaved by the protein endonuclease Dicer into short fragments of 21 to 25 nucleotide pairs (miRNA), which bind to the RISC protein complex (RNA-induced silencing complex) in the cytoplasm, after which the target mRNA is degraded and translation is blocked [14, 15]. Therapeutic agents that exhibit antiviral activity against viral hepatitis C (SPC3649), viral hepatitis B (NucB1000), Ebola hemorrhagic fever (TKM-Ebola), as well as a number of other viral infections are currently undergoing laboratory and clinical trials [16, 17]. There is a proven antiviral effect of small interfering RNA (siRNA) against animal viral pathogens such as Marek’s virus disease, foot and mouth disease, transmissible swine gastroenteritis and o’nyong-nyong viral fever [18‒21]. The development and use of new antiviral siRNA compositions, along with the existing ones, will make it possible to more effectively limit the spread of viral pathogens in the human population [22].

One of the approaches in the development of anti-influenza agents is the use of specific siRNA complementary to the messenger RNA (mRNA) of the target cellular genes. This method is mediated by the fact that influenza virus has a propensity for high mutational variability [23]. On this basis, it is more appropriate in this case to influence the expression of cellular genes whose protein products contribute to the reproduction of influenza virus in the cell, due to the fact that the risk of forming an alternative viral reproductive pathway is low [24]. We selected the following cellular target genes for such an evaluation: NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10. The NAA10 gene encodes the expression of NαA protein (N-terminal acetyltransferase), which is required for post-translational modification of proteins, including viral proteins. Acetylation of influenza virus proteins leads to increased viral virulence [22]. The PRPS1 gene encodes the expression of the PRPS1 protein, which catalyzes the phosphoribosylation of ribose-5-phosphate to 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate. This is essential for the biosynthesis of purine bases, particularly adenine, which is a component of viral RNA (vRNA) [25]. The NXF1 gene also encodes the expression of the protein of the same name and is involved in the process of exporting molecules from the nucleoplasm to the cytoplasm. The NS1 viral protein is able to bind to the TAP/NXF1 axis, which will promote the export of viral mRNA from the nucleus [26].

Approaches aimed at preventing viral inoculation and associated with the suppression of cellular genes expressing proteins critical for viral reproduction are of particular interest. Based on the above, the aim of the present study was to induce siRNA-mediated suppression of NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10 gene activity to evaluate the subsequent prophylactic and viral inhibitory effect of siRNA.

Materials and methods

Small interfering RNA. Nucleotide sequence analysis for subsequent siRNA selection was performed using Geneious (Geneious, USA) and siDirect 2.1 (University of Tokyo, Japan) programs. Geneious was used to align mRNA transcripts of target genes and then siRNA selection was carried out using siDirect 2.1 program. Synthesis of siRNA was carried out at Syntol (Moscow, Russia).

Viruses. Antigenic variants of influenza A virus: A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/WSN/33 (H1N1) and A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1) were obtained from the virus collection of the I.I. Mechnikov Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera. The multiplicity of infection used in the study (MOI) was 0.01.

Determination of viral titer. Viral activity was assessed by the maximum dilution of virus-containing fluid at which the endpoint of visual manifestation of cytopathic effect (CPE) in A549 cell culture was determined [27]. Viral titer values are given in TCD50/mL (tissue cytotoxic doses/mL).

Cell lines. The MDCK cell line representing canine renal tubule epithelium (Institut Pasteur, France) and the A549 cell line, human carcinoma alveolar-basal epithelial cells (ATCC-CCL-185 collection, USA), were used. Detailed culture conditions for the cell lines used are presented in our earlier study [28].

Methyl tetrazolium test (MTT test). The cytotoxic effect of siRNA was evaluated using the colorimetric MTT test. Detailed conditions for the MTT test are also presented in our earlier study [28]. Similar to the study by M. Estrin et al., the survival threshold of transfected cells was 70% of the survival of negative controls [29].

Transfection of siRNA into cell culture. siRNA transfection was performed in cell line A549 when 70% of the cell monolayer was reached (S wells – 2 cm2, seeding concentration of cells per well 2.5 × 105. The amount of miRNA substance was 0.25 μg per well2). At the initial stage, Geneject40 reagent (Molecta, Russia)2 and Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were mixed and then added to the siRNA and Opti-MEM mixture. The resulting complex was incubated for 15 min at 25 °C. During the incubation time, cells were washed with Hanks’ solution (PanEco, Russia) and serum-free Opti-MEM medium. As a non-specific control, siRNA L2, directed to the firefly luciferase gene, was used. It was developed and tested earlier by PhD Faizuloev E.B. to exclude the non-specific effect of other siRNAs, as well as to assess their effectiveness [30].

Inoculation of cells transfected with influenza virus. After 4 h from the moment of transfection we removed the supporting medium from the wells with transfected cells and inoculated 0.5 mL of virus-containing liquid with 0.01 MOI each, after which we put the cells back into the CO2-incubator.

Nucleic acid extraction. Total RNA was isolated from cell lysate using the Ribosorb kit (Amplisens, Russia) according to the service protocol. The obtained RNA was stored at −70 °C.

Reverse transcription reaction. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using an RT-1 commercial reagent kit (Syntol, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The reaction RT mixture with the isolated RNA was incubated in the Thermit thermostat (DNA-Technology, Russia) at the temperature and time regime of 37 °C for 60 min and 95 °C for 5 min.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The dynamics of vRNA concentration was assessed by real-time PCR (qPCR) with a set of primers specific for the M gene [31]. A set of reagents for PCR in the presence of EVA Green dye and ROX reference dye (Syntol) was used. The qPCR reaction was performed in the DT-96 thermal cycler (DNA-Technology, Russia) at the following settings: 95 °C – 5 min (1 cycle); 62 °C – 40 s, 95 °C – 15 s (40 cycles).

Evaluation of gene expression changes. The Pfaffl method was used to analyze the data obtained during qPCR and to assess the change in expression of target genes [32].

Ethical Approval. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Russian Ministry of Health (Sechenov University) (protocol No. 04-21 of 18.02.2021).

Statistical processing of data. The reliability of the final results was assessed using the statistical nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum criterion and Microsoft Excel 2013 software (Microsoft, USA) [33]. The difference was considered reliable at the level of statistical significance p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Determination of the values of cytotoxic action of siRNAs

On the 1st day from the moment of infection an acceptable level of survival was observed with all siRNAs, but on the 2nd day the survival rate was higher in cells treated with siRNAs: NXF1.1, PRPS1.2 and NAA10.1, and amounted to 77.0 ± 3.0, 86.0 ± 1.5 and 72.0 ± 4.0%, respectively. It should be noted that by the 3rd day from the moment of transfection of the mentioned complexes there was a pronounced increase in cell viability, exceeding this index in relation to other siRNAs. The obtained results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Percent of viable cells relative to control after siRNA transfection

Таблица 1. Процент жизнеспособных клеток по отношению к контролю после трансфекции миРНК

siRNA миРНК | 1st day 1-е сутки | 2nd day 2-е сутки | 3rd day 3-и сутки |

NXF1.1 | 77.0 ± 3.0 | 67.0 ± 1.0 | 71.0 ± 2.0 |

NXF1.2 | 73.0 ± 2.0 | 60.0 ± 4.0 | 67.0 ± 7.0 |

PRPS1.1 | 101.0 | 65.0 ± 8.0 | 71.0 ± 6.0 |

PRPS1.2 | 86.0 ± 1.5 | 67.0 ± 2.0 | 79.0 ± 3.0 |

NAA10.1 | 72.0 ± 4.0 | 70.0 ± 3.0 | 83.0 ± 4.0 |

NAA10.2 | 116.0 ± 8.0 | 65.0 ± 3.0 | 81.0 ± 1.0 |

siL2 | 83.0 ± 2.0 | 86.0 ± 4.0 | 92.0 ± 3.0 |

K− (non-transfected) K− (нетрансф.) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Note. The survival rate of untreated cells (negative control) was taken as 100%. The threshold value of survival was set at 70%. Names of complexes and the least toxic values based on cell viability reduction are marked in bold font.

Примечание. За 100% принята оценка выживаемости необработанных клеток (отриц. контроль). Пороговое значение выживаемости установлено на уровне 70%. Жирным шрифтом выделены наименования комплексов и наименее токсичные значения снижения жизнеспособности клеток.

Determination of the targeting effect of the siRNAs used

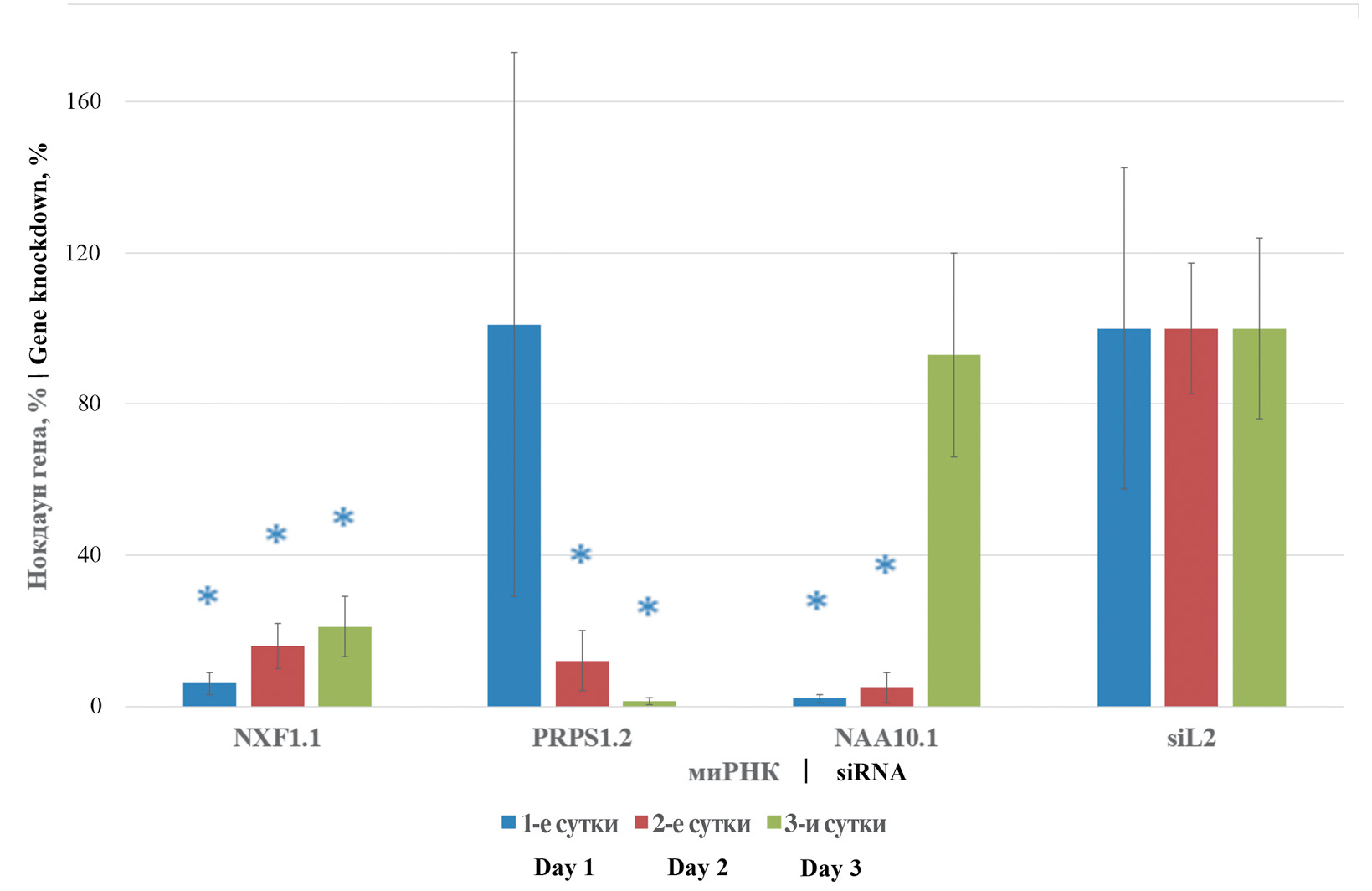

NXF1.1, PRPS1.2 and NAA10.1 were the siRNAs selected for further study. Their targeted action was evaluated for 3 days on A549 cell culture. It was found that transfection of NXF1.1 siRNA caused a significant decrease in the amount of transcription products of the same gene to the level of 6.0, 16.0 and 21.0% on days 1, 2 and 3, respectively, compared to the values obtained when analyzing cells transfected with nonspecific siL2 siRNA. A similar result was obtained with NAA10.1 siRNA, where the significant level of target gene transcription products within 2 days of transcription was 2.0 and 5.0% on the 1st and 2nd days, respectively, relative to the values of the nonspecific control group. On the 3rd day from the moment of transfection the percentage level of NAA10 gene transcripts reached similar values to the cells treated with siL2. PRPS1.2 siRNA induced a significant decrease in the percentage level of target gene expression on the 2nd and 3rd day to 12.0 and 1.3%, respectively. In addition to the low toxic effect, the inherent requirement of siRNA application is the suppression of target gene expression within the required time interval. At the present stage of the study, it was found that the use of the indicated siRNA resulted in a stable decrease in the level of transcripts of the indicated genes. The results are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Dynamic changes in NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10 gene transcripts.

siRNA and their target cellular genes of the same name are shown on the X-axis; % change in transcript level is shown on the Y-axis. Pfaffl test data are presented in %. * ‒ p ≤ 0.05.

Рис. 1. Изменение транскриптов генов NXF1, PRPS1 и NAA10 в динамике.

На оси абсцисс представлены миРНК и их одноименные целевые клеточные гены; на оси ординат ‒ процент изменения уровня транскрипта. Данные критерия Пфаффля представлены в процентах. * ‒ р ≤ 0,05.

The assessment of cell survival and the level of dynamics of target gene transcripts makes it clear that the used siRNAs do not cause excessive cytopathic effect on the tested cell line. The results obtained allow using NXF1.1, PRPS1.2 and NAA10.1 siRNA to further evaluate the prophylactic effect against different genetic variants of influenza A virus.

Evaluation of the antiviral effect of the siRNAs used

When evaluating the antiviral effect of the used siRNAs at day 1 from the time of transfection, it was found that lipofection of NXF1.1 siRNA leads to a decrease in the viral titer of A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1), and A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) strains by 3.5, 2.3, and 1.6 log10 TCID50/mL, respectively, relative to the viral titer level in cells treated with nonspecific siRNA. The amount of vRNA was decreased by 1088.0, 11.2 and 33.4-fold with this siRNA, respectively, compared to the nonspecific control group. On the 2nd day of using NXF1.1 siRNA, the index of viral activity for the indicated siRNA decreased by 3.2, 3.2 and 3.0 log10 TCID50/mL, and the amount of vRNA decreased by 633.4, 6.4 and 25.2 times, respectively, for the indicated strains relative to the nonspecific control group. Further, on the 3rd day, viral titer decreased by 2.2 and 2.0 log10 TCID50/mL in cells infected with strains A/Brisbane/59/07 and A/WSN/1933 (H1N1), and vRNA decreased by 8.3- and 30.2-fold, respectively.

PRPS1.2 siRNA transfection reduced viral replication of A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1), and A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) strains by 2.3, 2.1, and 2.1 log10 TCID50/mL on day 1, and vRNA by 2917.0, 10.8 and 33.4-fold, respectively. On the 2nd day from the time of transfection, the viral titer level decreased by 3.2, 0.7 and 1.2 log10 TCID50/mL, and vRNA decreased by 5059.4, 25.2 and 17.4-fold, respectively. After 72 h from the time of transfection, the viral levels were reduced by 2.2, 1.4 and 2.0 log10 TCID50/mL, respectively.

The use of NAA10.1 siRNA on the 1st day after transfection induced a decrease in the viral titer of A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1) and A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) strains by 1.6, 2.1 and 2.3 log10 TCID50/mL, respectively, relative to the nonspecific control group. The level of vRNA in this case decreased 141.3, 12.1, 16.6-fold, respectively. On the 2nd day after transfection, the viral titer decreased by 1.2 and 2.3 log10 TCID50/mL, respectively, in cell cultures, A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1) and A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) strains, and the amount of vRNA decreased 455.1-fold, 18.6-fold and 29.2-fold for A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1) and A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) strains, respectively. On day 3 after NAA10.1 lipofection, vRNA levels decreased 141.3-fold, 6.1-fold and 27.0-fold, respectively. The obtained data are presented in Fig. 2 and Table 2.

Fig. 2. Antiviral effect of siRNAs specific to the NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10 cell genes.

а ‒ A/California/7/09 (H1N1); b ‒ A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1); c ‒ A/WSN/1933 (H1N1); on the X-axis ‒ siRNA and their target cellular genes of the same name; on the Y-axis ‒ the viral titer log10 TCID50/mL relative to the viral and nonspecific control). * ‒ p < 0.05 relative to the nonspecific control siL2.

Рис. 2. Противовирусный эффект миРНК, специфичных к клеточным генам NXF1, PRPS1 и NAA10.

а ‒ A/California/7/09 (H1N1); б ‒ A/Brisbane/59/07 (H1N1); в ‒ A/WSN/1933 (H1N1). По оси абсцисс ‒ миРНК и их одноименные целевые клеточные гены; по оси ординат ‒ показатель вирусного титра lg ТЦД50/мл относительно вирусного и неспецифического контроля. * ‒ р < 0,05 относительно неспецифического контроля siL2.

Table 2. Antiviral effect of siRNAs directed to the NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10 genes on the dynamics of the amount of vRNA of the influenza virus A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/Brisbane/59/07 and A/WSN/1933 (H1N1)

Таблица 2. Влияние противовирусного эффекта миРНК, направленных к генам NXF1, PRPS1 и NAA10, на динамику количества вРНК вируса гриппа A/California/7/09 (H1N1), A/Brisbane/59/07 и A/WSN/1933 (H1N1)

Gene Ген | siRNA миРНК | Influenza A virus vRNA reduction rate (multiplicity relative to siL2) at 0.01 MOI Показатель снижения вРНК вируса гриппа А (кратность по отношению к siL2) при мн.з. 0,01 | ||

1st day 1-е сутки | 2nd day 2-е сутки | 3rd day 3-и сутки | ||

A/California/7/09 (H1N1) | ||||

NXF1 | NXF1.1 | 1088.0 | 633.4 | 423.9 |

PRPS1 | PRPS1.2 | 2917.1 | 5059.4 | 1771.1 |

NAA10 | NAA10.1 | 8.6 | 455.1 | 141.3 |

siL2 | 21 012 866 | 19 581 834 721 | 24 581 834 721 | |

A/Brisbane/59/07 | ||||

NXF1 | NXF1.1 | 11.2 | 6.4 | 8.3 |

PRPS1 | PRPS1.2 | 10.8 | 25.2 | 15.5 |

NAA10 | NAA10.1 | 12.1 | 18.6 | 6.1 |

siL2 | 195 184 | 1 837 130 | 23 156 335 | |

A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) | ||||

NXF1 | NXF1.1 | 33.4 | 33.6 | 30.2 |

PRPS1 | PRPS1.2 | 10.4 | 17.4 | 40.3 |

NAA10 | NAA10.1 | 16.6 | 29.2 | 27.0 |

siL2 | 371 038 | 2 647 184 | 41 839 472 | |

Note. The results were calculated relative to cells with nonspecific siRNA L2. Data for the nonspecific siL2 control are given as the number of vRNA units/mL. Values for which p < 0.05 are shown in bold.

Примечание. Расчет результатов проводился относительно клеток с неспецифической миРНК L2. Данные для неспецифического контроля siL2 даны в значении количество единиц вРНК/мл. Жирным шрифтом выделены значения, для которых р < 0,05.

Discussion

From the moment of its discovery, the RNA interference mechanism was immediately used as one of the tools to regulate viral reproduction in in vitro and in vivo models. Moreover, the classical approach to designing agents based on the RNA interference mechanism was the use of viral genome regions as targets, which is reflected in one of the earliest studies by Q. Ge et al. In this study, the authors infected mice with influenza A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) virus and intranasally inoculated siRNA to the viral NP gene, which caused a 60-fold decrease in reproduction [34]. The results of the study by H.Y. Sui et al. show that using siRNAs directed to the conserved sequence of the gene expressing the M2 viral protein, inhibition of reproduction of highly virulent A/Hong Kong/486/97 (H5N1) by 3 times was observed [35]. A study conducted by J. Piasecka et al. examined the antiviral effect of siRNA-mediated inhibition of NP protein formation of influenza viruses A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) and A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), during which a decrease in viral reproduction up to 85% compared to the control group was observed [36].

At the same time, influenza A viruses are highly prone to mutational variability as a result of substitutions, deletions, insertions of nucleotide sequence regions, or reassortment, which leads to drug resistance [23]. On this basis, the development of new prophylactic and therapeutic approaches using siRNA targeted to cellular targets has a number of advantages: such agents can have both prophylactic and therapeutic potential; it is possible to design and synthesize a siRNA-based drug within a few hours; siRNA-based drugs can be used in combination with other antiviral drugs to synergize their effect; siRNA targeted to cellular genes transcribing protein products key for the development of antiviral drugs can be used in combination with other antiviral drugs; siRNA can be used in combination with other antiviral drugs to synergize their effect; siRNA targeted to cellular genes transcribing protein products key for the development of therapeutic approaches. Based on these criteria, it is important to search for cellular target genes whose knockdown will inhibit the reproduction of viruses of closely or distantly related taxonomic groups. In the present study, the antiviral effect of prophylactic transfection of siRNAs targeting the cellular genes NXF1, PRPS1 and NAA10 was assessed. The results suggest that nuclear import and export processes, phosphoribosylation of ribose-5-phosphate to 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate, and posttranslational modification of proteins may play important roles in influenza virus reproduction [37‒39]. Inhibition of translation of the genes under consideration leads to a decrease in viral reproduction according to the results of such methods as CPE titration and qPCR. It was shown that along with the decrease of the viral titer index, starting from the moment of lipofection of the studied siRNA, there was also a decrease in the amount of viral RNA within 3 days. The most effective decrease of viral reproduction was observed at suppression of the NXF1 gene in the 1st day from the moment of transfection of all specifically inhibitory siRNA: decrease of viral titer by 2.0‒3.2 log10 TCID50/mL and decrease of vRNA amount by 11.2‒1088.0 times. Temporary disruption of influenza virus reproduction as a result of siRNA-mediated blockage of nuclear import and export as a result of NXF1 gene silencing resulted in a more pronounced antiviral effect compared with other cellular genes investigated in this study. This result may be mediated by the fact that during their reproduction, influenza viruses carry out part of the replicative cycle in the nucleoplasm, translocating through the nuclear pore complex in the nucleus membrane, while ribosylation and posttranslational modification of proteins may be carried out by other pathways [40‒42].

In parallel, a number of studies have noted the importance of the NXF1 gene/protein in the reproductive cycle of other viruses. Thus, the study by M. Mei et al. noted the key importance of NXF1 in nuclear export of mRNA for SARS-CoV-2; however, structure-guided mutagenesis of the acidic site (D33, E36, E37 and E41) on the surface of the N-terminal domain of Nsp1, which mediates interaction with NXF1, resulted in blockage of nuclear export [43]. A similar defect in the binding of NS1 of influenza A virus to the NXF1•NXT1 axis leads to the release of mRNAs encoding a number of immune factors from the nucleus and, as a consequence, to a decrease in viral activity, as presented in the study by K. Zhang et al. [44]. No less important is the role of NXF1 in the life cycle of Ebola virus shown in a study by L. Wendt et al. where the authors carried out co-immunoprecipitation reaction and double immunofluorescence analysis to characterize the interaction of NXF1 with viral proteins and vRNA. The NP viral protein was found to interact with the RNA-binding domain of NXF1 and to compete with RNA for this interaction. A minigenomic system was also used in this study, where NXF1 gene knockdown was observed. Against the background that mRNA levels in cells with NXF1 dysfunction were comparable to control cells, the authors suggested that NXF1 is important for nuclear export of mRNA to ribosomes for efficient mRNA translation [45]. Unspliced HIV-1 RNA is used for the subsequent translation of viral proteins, but before that it must be translocated from the nucleoplasm into the cytoplasm. In a study by J. Chen et al. which utilized in situ hybridization, it was found that NXF1 is involved for nuclear export used by HIV-1 [46].

Along with transcription and translation, mRNA translocation through the nuclear pore complex (NPC), of which NXF1 is a structural component, appears to be an important regulatory step in gene expression of a number of viral families [47]. Based on the results obtained in the study, as well as the literature sources reviewed above, it can be concluded that the protein product of NXF1 gene expression plays an important role in the reproduction of viruses belonging to different taxonomic groups. In addition to the NXF1 gene, other genes that form NPCs are also targets whose silencing can lead to decreased viral reproduction. For example, our earlier study showed a correlation between reduced influenza A viral activity and inhibition of expression of the Nup98 and Nup205 genes, which also encode the formation of NPC nucleoporin proteins [48]. Therefore, siRNA-mediated disruption of the functional activity of certain NPC components can be considered as one of the promising options for the development of antiviral drugs targeting a wide range of viral infections.

The results obtained in the study clearly demonstrate that the prophylactic regimen of siRNA use reduces subsequent viral replication. The available data are consistent with the concept that prophylactic blockade of host cell factors important for viral replication by siRNA is able to disrupt the infectious process [49]. At the same time, it is important to understand that such an administration regimen requires precise timing of administration of the prophylactic drug. In view of this, it is also necessary to conduct studies aimed at optimizing and selecting the optimal conditions and timing for administration of the prophylactic drug.

Conclusion

The obtained data confirm that the genes encoding proteins forming the nuclear pore complex are promising targets for antiviral siRNAs. The knockdown of the expression of these proteins leads to a decrease in the reproduction of influenza viruses. Thus, the creation of antiviral drugs based on RNA interference is a promising vector for the development of anti-influenza drugs.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Past reported global human cases with highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) (HPAI H5N1) by country, 1997–2024. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/php/avian-flu-summary/chart-epi-curve-ah5n1.html

2 http://molecta.ru/wordpress/transfection

About the authors

Evgeny A. Pashkov

Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University); I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Author for correspondence.

Email: pashckov.j@yandex.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-5682-4581

Ph. D., assistant of microbiology, virology and immunology department of Sechenov University; junior researcher laboratory of virology applied of I. Mechnikov Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Russian Federation, 119991, Moscow; 105064, MoscowDmitry A. Shikvin

Moscow State University of Fine Chemical Technologies

Email: carrypool@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0009-0005-9874-2081

student of the Department of Biotechnology and Industrial Pharmacy of the Institute of Fine Chemical Technologies named after M.V. Lomonosov

Russian Federation, 119454, MoscowGeorge A. Pashkov

Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University); I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Email: georgp2004@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0392-9969

student of the Institute of Children Health

Russian Federation, 119991, Moscow; 105064, MoscowFiraya G. Nagieva

Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University)

Email: fgn42@yandex.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8204-4899

MD, private-docent, The Head of laboratory of hybrid cell cultures

Russian Federation, 119991, MoscowEkaterina A. Bogdanova

I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Email: bogdekaterin@yandex.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-5620-1843

Ph. D., private-docent of Microbiology, Virology and Immunology department

Russian Federation, 105064, MoscowAnatoly S. Bykov

I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Email: drbykov@bk.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-8099-6201

MD, Professor of Microbiology, Virology and Immunology department

Russian Federation, 105064, MoscowEvgeny P. Pashkov

I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Email: 9153183256@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4963-5053

MD, Professor of Microbiology, Virology and Immunology department

Russian Federation, 105064, MoscowOxana A. Svitich

Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University); I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Email: svitichoa@yandex.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1757-8389

Corresponding member of RAS, MD, The head of I. Mechnikov Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera; Professor of Microbiology, Virology and Immunology department of Sechenov University

Russian Federation, 119991, Moscow; 105064, MoscowVitaly V. Zverev

Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University); I.I. Mechnikov Scientific and Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera

Email: vitalyzverev@outlook.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-0017-1892

Academician of RAS, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Scientific Adviser of I. Mechnikov Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera; Professor, The Leader of Microbiology, Virology and Immunology department of Sechenov University

Russian Federation, 119991, Moscow; 105064, MoscowReferences

- Purcell R., Giles M.L., Crawford N.W., Buttery J. Systematic review of avian influenza virus infection and outcomes during pregnancy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025; 31(1): 50–6. http://doi.org/10.3201/eid3101.241343

- Bin N.R., Prescott S.L., Horio N., Wang Y., Chiu I.M., Liberles S.D. An airway-to-brain sensory pathway mediates influenza-induced sickness. Nature. 2023; 615(7953): 660–7. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05796-0

- Kenney A.D., Aron S.L., Gilbert C., Kumar N., Chen P., Eddy A., et al. Influenza virus replication in cardiomyocytes drives heart dysfunction and fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 2022; 8(19): eabm5371. http://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abm5371

- Conrad A., Valour F., Vanhems P. Burden of influenza in the elderly: a narrative review. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2023; 36(4): 296–302. http://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000931

- Watanabe T. Renal complications of seasonal and pandemic influenza A virus infections. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013; 172(1): 15–22. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-012-1854-x

- van de Veerdonk F.L., Wauters J., Verweij P.E. Invasive aspergillus tracheobronchitis emerging as a highly lethal complication of severe influenza. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020; 202(5): 646–8. http://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202005-1883ED

- Feys S., Cardinali-Benigni M., Lauwers H.M., Jacobs C., Stevaert A., Gonçalves S.M., et al. Profiling bacteria in the lungs of patients with severe influenza versus COVID-19 with or without aspergillosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024; 210(10): 1230–42. http://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202401-0145OC

- Białka S., Zieliński M., Latos M., Skurzyńska M., Żak M., Palaczyński P., et al. Severe bacterial superinfection of influenza pneumonia in immunocompetent young patients: case reports. J. Clin. Med. 2024; 13(19): 5665. http://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13195665

- Pleguezuelos O., James E., Fernandez A., Lopes V., Rosas L.A., Cervantes-Medina A., et al. Efficacy of FLU-v, a broad-spectrum influenza vaccine, in a randomized phase IIb human influenza challenge study. NPJ Vaccines. 2020; 5(1): 22. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-020-0174-9

- Isakova-Sivak I., Rudenko L. Next-generation influenza vaccines based on mRNA technology. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025; 25(1): 2–3. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00562-0

- Hodgson D., Sánchez-Ovando S., Carolan L., Liu Y., Hadiprodjo A.J., Fox A., et al. Quantifying the impact of pre-vaccination titre and vaccination history on influenza vaccine immunogenicity. Vaccine. 2025; 44: 126579. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126579

- Gaitonde D.Y., Moore F.C., Morgan M.K. Influenza: diagnosis and treatment. Am. Fam. Physician. 2019; 100(12): 751–8.

- Li Y., Huo S., Yin Z., Tian Z., Huang F., Liu P., et al. The current state of research on influenza antiviral drug development: drugs in clinical trial and licensed drugs. mBio. 2023; 14(5): e0127323. http://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01273-23

- Wang J., Li Y. Current advances in antiviral RNA interference in mammals. FEBS J. 2024; 291(2): 208–16. http://doi.org/10.1111/febs.16728

- Traber G.M., Yu A.M. RNAi-based therapeutics and novel RNA bioengineering technologies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2023; 384(1): 133–54. http://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.122.001234

- Qureshi A., Tantray V.G., Kirmani A.R., Ahangar A.G. A review on current status of antiviral siRNA. Rev. Med. Virol. 2018; 28(4): e1976. http://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.1976

- Chokwassanasakulkit T., Oti V.B., Idris A., McMillan N.A. SiRNAs as antiviral drugs – Current status, therapeutic potential and challenges. Antiviral. Res. 2024; 232: 106024. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2024.106024

- Wang L., Dai X., Song H., Yuan P., Yang Z., Dong W., et al. Inhibition of porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus infection in porcine kidney cells using short hairpin RNAs targeting the membrane gene. Virus Genes. 2017; 53(2): 226–32. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-016-1409-8

- Lambeth L.S., Zhao Y., Smith L.P., Kgosana L., Nair V. Targeting Marek’s disease virus by RNA interference delivered from a herpesvirus vaccine. Vaccine. 2009; 27(2): 298–306. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.023

- Chen W., Liu M., Jiao Y., Yan W., Wei X., Chen J., et al. Adenovirus-mediated RNA interference against foot-and-mouth disease virus infection both in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 2006; 80(7): 3559–66. http://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.80.7.3559-3566.2006

- Keene K.M., Foy B.D., Sanchez-Vargas I., Beaty B.J., Blair C.D., Olson K.E. RNA interference acts as a natural antiviral response to O’nyong-nyong virus (Alphavirus; Togaviridae) infection of Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004; 101(49): 17240–5. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0406983101

- Ahmed F., Kleffmann T., Husain M. Acetylation, methylation and allysine modification profile of viral and host proteins during influenza A virus infection. Viruses. 2021; 13(7): 1415. http://doi.org/10.3390/v13071415

- Izumi H. Conformational variability prediction of influenza virus hemagglutinins with amino acid mutations using supersecondary structure code. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2025; 2870: 63–78. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-4213-9_5

- Lesch M., Luckner M., Meyer M., Weege F., Gravenstein I., Raftery M., et al. RNAi-based small molecule repositioning reveals clinically approved urea-based kinase inhibitors as broadly active antivirals. PLoS Pathog. 2019; 15(3): e1007601. http://doi.org/101371/journal.ppat.1007601

- Li X., Berg N.K., Mills T., Zhang K., Eltzschig H.K., Yuan X. Adenosine at the interphase of hypoxia and inflammation in lung injury. Front. Immunol. 2021; 11: 604944. http://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.604944

- Read E.K., Digard P. Individual influenza A virus mRNAs show differential dependence on cellular NXF1/TAP for their nuclear export. J. Gen. Virol. 2010; 91(Pt. 5): 1290–301. http://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.018564-0

- Ramakrishnan M.A. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J. Virol. 2016; 5(2): 85–6. http://doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v5.i2.85

- Pashkov E.A., Samoilikov R.V., Pryanikov G.A., Bykov A.S., Pashkov E.P., Poddubikov A.V., et al. In vitro immunomodulatory effect of siRNA complexes in the influenza infection. Russian Journal of Immunology. 2023; 26(4): 457–62. http://doi.org/10.46235/1028-7221-13984-IVI https://elibrary.ru/byxobk (in Russian)

- Estrin M.A., Hussein I.T.M., Puryear W.B., Kuan A.C., Artim S.C., Runstadler J.A. Host-directed combinatorial RNAi improves inhibition of diverse strains of influenza A virus in human respiratory epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2018; 13(5): e0197246. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197246

- Faizuloev E.B. Study of antiviral activity of antisense RNAs and ribozymes in relation to infection caused by the Aleutian mink disease virus: Diss. Moscow; 2002. (in Russian)

- Lee H.K., Loh T.P., Lee C.K., Tang J.W., Chiu L., Koay E.S. A universal influenza A and B duplex real-time RT-PCR assay. J. Med. Virol. 2012; 84(10): 1646–51. http://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23375

- Bustin S.A., Benes V., Nolan T., Pfaffl M.W. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR – a perspective. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005; 34(3): 597–601. http://doi.org/10.1677/jme.1.01755

- Howard C.W., Zou G., Morrow S.A., Fridman S., Racosta J.M. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney odds ratio: A statistical measure for ordinal outcomes such as EDSS. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022; 59: 103516. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2022.103516

- Ge Q., Filip L., Bai A., Nguyen T., Eisen H.N., Chen J. Inhibition of influenza virus production in virus-infected mice by RNA interference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004; 101(23): 8676–81. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0402486101

- Sui H.Y., Zhao G.Y., Huang J.D., Jin D.Y., Yuen K.Y., Zheng B.J. Small interfering RNA targeting M2 gene induces effective and long-term inhibition of influenza A virus replication. PLoS One. 2009; 4(5): 5671. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005671

- Piasecka J., Lenartowicz E., Soszynska-Jozwiak M., Szutkowska B., Kierzek R., Kierzek E. RNA secondary structure motifs of the influenza A virus as targets for siRNA-mediated RNA interference. Mol. Ther. Nucleic. Acids. 2020; 19: 627–42. http://doi.org/10.1016/j/omtn.2019.12.018

- Zhou Y., Liu Y., Gupta S., Paramo M.I., Hou Y., Mao C., et al. A comprehensive SARS-CoV-2-human protein-protein interactome reveals COVID-19 pathobiology and potential host therapeutic targets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023; 41(1): 128–39. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01474-0

- Hu J., Zhang L., Liu X. Role of post-translational modifications in influenza A virus life cycle and host innate immune response. Front. Microbiol. 2020; 11: 517461. http://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.517461

- Zhang K., Cagatay T., Xie D., Angelos A.E., Cornelius S., Aksenova V., et al. Cellular NS1-BP protein interacts with the mRNA export receptor NXF1 to mediate nuclear export of influenza virus M mRNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 2024; 300(11): 107871. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107871

- Esparza M., Bhat P., Fontoura B.M. Viral-host interactions during splicing and nuclear export of influenza virus mRNAs. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022; 55: 101254. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2022.101254

- Dawson A.R., Wilson G.M., Coon J.J., Mehle A. Post-Translation Regulation of Influenza Virus Replication. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2020; 7(1): 167–87. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-010320-070410

- Husain M. Influenza A virus and acetylation: the picture is becoming clearer. Viruses. 2024; 16(1): 131. http://doi.org/10.3390/v16010131

- Mei M., Cupic A., Miorin L., Ye C., Cagatay T., Zhang K., et al. Inhibition of mRNA nuclear export promotes SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2024; 121(22): e2314166121. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2314166121

- Zhang K., Xie Y., Muñoz-Moreno R., Wang J., Zhang L., Esparza M., et al. Structural basis for influenza virus NS1 protein block of mRNA nuclear export. Nat. Microbiol. 2019; 4(10): 1671–9. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0482-x

- Wendt L., Brandt J., Bodmer B.S., Reiche S., Schmidt M.L., Traeger S., et al. The Ebola virus nucleoprotein recruits the nuclear RNA export factor NXF1 into inclusion bodies to facilitate viral protein expression. Cells. 2020; 9(1): 187. http://doi.org/10.3390/cells9010187

- Chen J., Umunnakwe C., Sun D.Q., Nikolaitchik O.A., Pathak V.K., Berkhout B., et al. Impact of nuclear export pathway on cytoplasmic HIV-1 RNA transport mechanism and distribution. mBio. 2020; 11(6): e01578–20. http://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01578-20

- Guo J., Zhu Y., Ma X., Shang G., Liu B., Zhang K. Virus infection and mRNA nuclear export. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023; 24(16): 12593. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612593

- Pak A.V., Pashkov E.A., Abramova N.D., Poddubikov A.V., Nagieva F.G., Bogdanova E.A., et al. Effect of antiviral siRNAs on the production of cytokines in vitro. Tonkie khimicheskie tekhnologii. 2022; 17(5): 384–93. https://doi.org/10.32362/2410-6593-2022-17-5-384-393 https://elibrary.ru/meflst (in Russian)

- Banerjee A., Mukherjee S., Maji B.K. Manipulation of genes could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection that causes COVID-19 pandemics. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 2021; 246(14): 1643–9. http://doi.org/10.1177/15353702211008106

Supplementary files