Detection and characterization of the Dezidougou virus (genus Negevirus) in mosquitoes (Ochlerotatus caspius) collected in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)

- Authors: Stepanyuk M.A.1, Legostaev S.S.1, Karelina K.V.1, Timofeeva N.F.2, Emtsova K.F.1, Ohlopkova O.V.1, Taranov O.S.1, Ternovoi V.A.1, Protopopov A.V.2, Loktev V.B.1, Svyatchenko V.A.1, Agafonov A.P.1

-

Affiliations:

- State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

- M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University

- Issue: Vol 70, No 1 (2025)

- Pages: 47-56

- Section: ORIGINAL RESEARCHES

- URL: https://virusjour.crie.ru/jour/article/view/16698

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.36233/0507-4088-280

- EDN: https://elibrary.ru/pbmmdx

- ID: 16698

Cite item

Abstract

Introduction. Monitoring and research on arthropod-borne microorganisms is important. Recently, with the development of next-generation sequencing methods, many previously unknown viruses have been identified in insects.

Aim of the study. Isolation of viruses from mosquitoes sampled in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), followed by the study of a new for Russia negevirus isolated from mosquitoes of the species Ochlerotatus caspius, including determination of its complete nucleotide sequence, phylogenetic and virological characteristics.

Materials and methods. Dezidougou virus isolation was performed on C6/36 (Aedes albopictus) cell culture. Electron microscopy was performed using a JEM 1400 electron microscope. Nucleotide sequence screening was performed by NGS on a high-throughput sequencer MiSeq, Illumina (USA). Full genome nucleotide sequence was determined by Sanger sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using GenBank database, using Vector NTI Advance 11 and MEGA 11 programs.

Results. The virus isolated from mosquitoes replicated efficiently in C6/36 cells, causing their death. However, it did not replicate in the mammalian cell cultures used. The isolated virus did not cause pathologic manifestations in suckling mice when infected intracerebrally. Electron microscopic examination of the purified virus-containing suspension showed the presence of spherical viral particles with a diameter of 45‒55 nm. The results of full genome sequencing identified it as belonging to Dezidougou virus, first isolated in Côte d’Ivoire. The nucleotide sequence of the genome of Yakutsk 2023 strain of Dezidougou virus was deposited in GenBank (PP975071.1).

Conclusion. Dezidougou virus of genus Negevirus was isolated and characterized for the first time in the Russian Federation. Further studies on the prevalence of negeviruses, their virological features, potential importance for public health and their impact on vector competence of vectors are important and promising.

Full Text

Introduction

Historically, there has been a special interest in arthropod-infecting viruses because of their involvement in the spread of viruses pathogenic to humans and animals. Initially, the term insect specific viruses (ISVs) referred to viruses of the genus Ortoflavivirus (family Flaviviridae) that could replicate only in insect cells but had a similar genome organization to orthoflaviviruses pathogenic to vertebrates [1, 2]. With the development of high-throughput sequencing methods, new ISVs have been identified [3, 4]. To date, the group of ISVs includes representatives of different families: Baculoviridae, Poxviridae, Iridoviridae, Ascoviridae, Polydnaviridae, the genome of which is represented by double-stranded DNA; Parvoviridae (single-stranded DNA); Reoviridae, Tetraviridae, Dicistroviridae, Nodaviridae, Picornaviridae, Flaviviridae (RNA(+)); Rhabdoviridae (RNA(−)) [1‒5].

Representatives of the genus Negevirus are found in different parts of the world and infect a wide range of hematophages (mosquitoes of the genera Culex, Aedes and Anopheles, as well as mosquitoes of the genus Lutzomyia). At the same time, negeviruses are genetically close to plant viruses from the genera Cilevirus, Higrevirus and Blunervirus (family Kitaviridae), which allowed us to hypothesize the role of plants in the natural transmission cycle of negeviruses [6, 7]. The genus Negevirus is named after the first fully characterized isolate of Negev virus [6]. More than 36 species of viruses, not including 30 unclassified viruses (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browse/), are currently classified as negeviruses.

Dezidougou virus (DEZV) was first isolated at the Pasteur Institute (Dakar, Senegal) from a population of mosquitoes Aedes aegypti collected near the village of Dezidougou, Côte d’Ivoire, in 1987 [6, 7]. Later, DEZV was found in different parts of the world: Europe, Africa, Central and South America [6, 8, 9]. Virions of negeviruses have a spherical shape with a diameter of 45‒50 nm [6]. The genome of negeviruses is represented by unsegmented single-stranded RNA with positive sense, 7‒10 kb in size. Most negeviruses have three open reading frames (ORF) flanked by non-translated regions at the 5’- and 3’-ends. Each ORF is separated by short intergenic regions, the largest frame ORF1 encodes viral polymerase, ORF2 encodes glycoprotein, and ORF3 encodes membrane proteins [7]. At the end of the viral genome, a poly(A)-tail is present, ranging from 13 to 52 nt in length. [6].

The aim of this study was to isolate viruses from mosquitoes sampled in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) and to study DEZV virus, new for Russia, isolated from mosquitoes of species Ochlerotatus caspius, including determination of its complete nucleotide sequence, phylogenetic and virological characterization.

Materials and methods

During the field period of 2023, 500 mosquitoes were captured on the territory of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) in the Saisarsky (62.029955/129.668761) and Central districts (62.009133/129.744127). The mosquitoes were transported in cooler bags on wet cloths at +4 °C and stored at −18‒24 °C. Mosquitoes were sorted according to phenotypic traits and pooled into pools of 10 individuals. The morphological keys for genus determination were the size of the individual, color of scales, length of legs and structure of the mouth apparatus. A fragment of 16S rRNA and a fragment of the COI gene of the mitochondrial genome were sequenced to determine the mosquito species. A total of 51 mosquito pools were examined.

Before homogenization, all mosquitoes were washed in 70% ethanol and then twice with water to remove potential surface microorganisms. The resulting pools of Ochlerotatus sp. mosquitoes were homogenized in 300 µl of saline solution on a TissueLyser LT homogenizer (Qiagen, The Netherlands).

Virus isolation was performed on the C6/36 (Aedes albopictus) cell culture, highly sensitive for ISVs [10‒12]. The monolayer was grown to 80‒90% confluency in a 24-well plate (Greiner, Austria) in DMEM F12 medium (Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA), 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco, USA) in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 28 °C. The culture was infected with filtered mosquito homogenates and incubated for 7 days, evaluating possible cytopathic effects (CPE). After that, the plates with cell monolayers were subjected to three freeze/thaw cycles, the obtained suspensions were clarified from cell debris by centrifugation at 8000g at 4 °C for 5 min and used for passaging (infection of fresh C6/36 cell monolayers similar to the above described). After detection of pronounced virus-specific CPE, the viral suspensions were used to infect monolayers of C6/36 cells grown in culture vials (Greiner, Austria). Determination of the infectious titer of the obtained virus-containing suspension was performed according to the standard method on C6/36 culture by micromethod with registration of the results by microscopy and MTT test [13, 14]. The titer was calculated using the Spearman‒Kerber method [15].

Light microscopy was performed using an Olympus CKX53 inverted microscope (Olympus, Japan), with fixation with an Olympus SC50 digital camera (Olympus, Japan) at ×200 magnification and digital processing in the Cellsens Standard program.

For electron microscopy, virus-containing culture medium was clarified from cells by centrifugation at 8000g for 10 min to remove residual cellular debris. The virus was concentrated using a VivaSpin centrifuge concentrator (Sartorius, Germany) for 30 min at 6000g. The concentrate was resuspended, fixed with formalin and applied as suspensions on copper grids coated with formvar substrate film and stabilized with carbon. The obtained drugs were stained with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate solution according to the generally accepted technique. The samples were examined using a JEM 1400 electron microscope (Jeol, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Image analysis and processing were performed using iTEM software package (SIS, Germany).

The ability of DEZV to infect mammalian cells was investigated on transplantable cultures: HEK-293A (human embryonic kidney cells), Vero E6 (green monkey kidney cells) and SPEV (pig embryonic kidney cells). A monolayer of cells in T-25 culture vials was infected with 0.1 mL of inoculum and incubated in DMEM F12 maintenance medium with 2% FBS (fetal bovine serum) for 10 days. The resulting cell lysates were tested for the presence of infectious viral progeny by titration on C6/36 cell culture.

The susceptibility of animals to DEZV was tested on 2‒3-day-old suckling mice. Animals infected intracerebrally with 0.02 mL of inoculum were monitored for the 21 days.

Screening for ISV nucleotide sequences was performed by high-throughput sequencing. Total RNA was extracted using the Extract RNA Reagent (Eurogen, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The aqueous phase obtained after addition of chloroform and subsequent centrifugation was collected and diluted 1 : 1 with freshly prepared 70% ethanol and purified on Cleanup Mini spin columns (Eurogen, Russia) and treated with Benzonaze (Merck, Germany) [16]. Synthesis of the first strand of cDNA was performed using the NEBNext Ultra Directional module (New England Biolabs Inc., USA). Second strand DNA synthesis was performed using UMI Second Strand Synthesis Module for QuantSeq FWD Illumina (Lexogen, Austria). Prepared dsDNA libraries were analyzed on a MiSeq high-throughput sequencer (Illumina, USA). Cutadapt (version 1.18) and SAMtools (version 0.1.18) were used to remove Illumina adapters and re-read sequences. Contigs were assembled de novo using the MIRA assembler (version 4.9.6).

The complete nucleotide sequence of DEZV RNA was determined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using primers (Appendix 1) complementary to the genome fragments of the virus under study. RT-PCR was performed in 15 µL of the reaction mixture in a C1000 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, USA). The obtained amplicons were separated by gel electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel in Tris-acetate buffer (Eurogen, Russia) with 0.1% ethidium bromide (Sisco Research Laboratories, India).

Sanger sequencing reaction was performed using BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA), on a 3500xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA). The obtained nucleotide sequences were aligned to prototype sequences using the UniproUGENE v. 1.48 software product. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the GenBank database. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using Vector NTI Advance 11 and MEGA 11 programs. Phylogenetic trees were built by maximum likelihood method using 500 bootstrap replicates.

The authors confirm compliance with institutional and national standards for the use of laboratory animals according to Consensus author guidelines for animal use 2010. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector» of Rospotrebnadzor (Protocol No. 02 of 03.04.2023).

Results

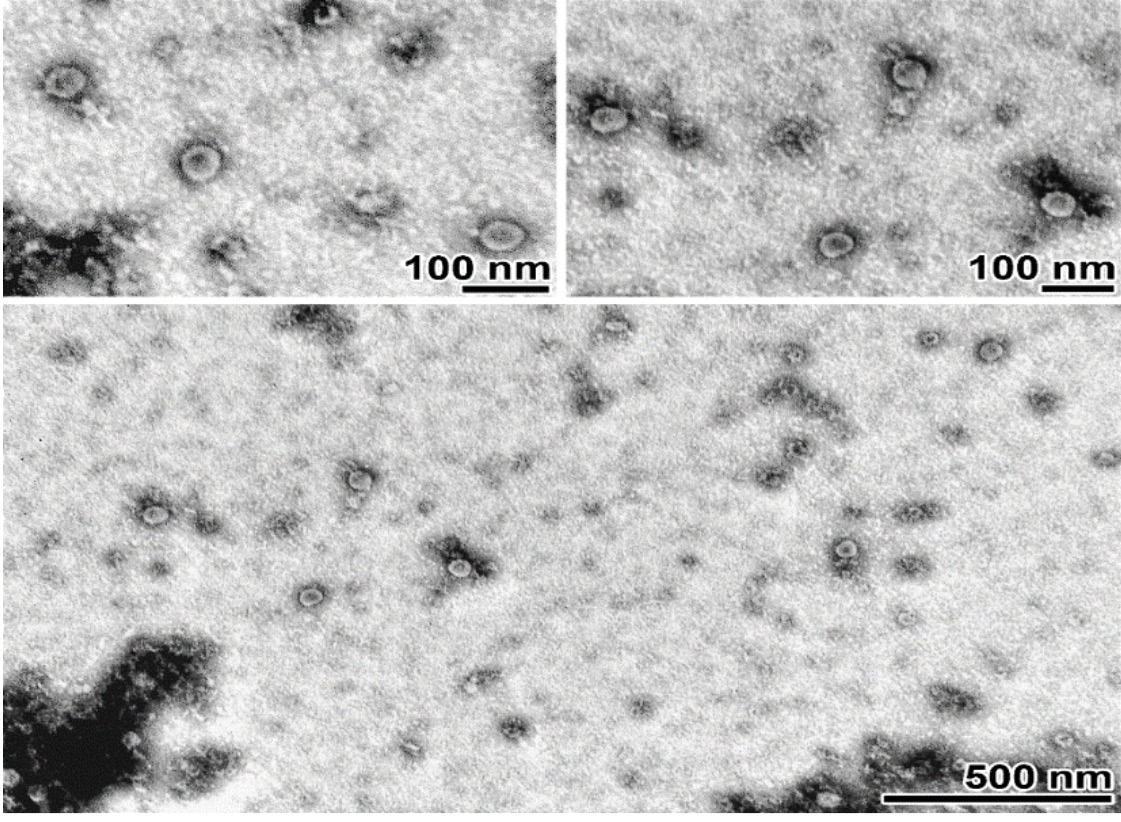

In an attempt to isolate viruses from homogenates of 51 mosquito pools, 3 consecutive passages were performed on C6/36 culture. When the 3rd passage was performed on a monolayer of C6/36 cells corresponding to one of the pools used for infection, cytopathic manifestations were recorded on the 5th day of incubation, which increased with further incubation. To confirm the presence of lytic-inducing virus, an additional 4th passage was performed on a confluent C6/36 monolayer. Fig. 1 shows microphotographs illustrating the presence of pronounced virus-specific CPE leading to 100% cell death by day 6 post-infection. The infectious activity of the isolated viral isolate was determined by titration on C6/36 cell culture and amounted to 7.1 log10 TCID50/mL. Electron microscopic examination was performed to determine the shape and size of viral particles. The negatively stained virus suspension contained particles predominantly 48‒52 nm in diameter, round in shape, with a more electron-dense area in the central part (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Light microscopy (×200) of C6/36 cell culture infected with DEZV Yakutsk 2023 strain 120 hours after infection.

On the left is a control of C6/36 cell culture.

Рис. 1. Световая микроскопия (×200) культуры клеток С6/36, инфицированной штаммом DEZV Yakutsk 2023, через 120 ч после инфицирования.

Слева представлен контроль культуры клеток С6/36.

Fig. 2. Transmission electron microscopy of a purified virus suspension.

Rounded particles with a diameter of 45‒55 nm and an electron-dense region in the central part. Contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate. The scale is indicated on images.

Рис. 2. Просвечивающая электронная микроскопия очищенной суспензии вируса.

Частицы округлой формы диаметром 45‒55 нм и электронно-плотной областью в центральной части. Контрастирование 2% уранилацетатом. Бар указан на снимках.

To determine the potential ability of the viral isolate to replicate in mammalian cells, cell cultures Vero E6, HEK-293A and SPEV were infected at a multiplicity of 10 TCID50/cell and incubated for 10 days. No virus-specific effects on cell cultures were detected. Cell lysates of the above cultures were titrated on C6/36 culture. Infectious virus was detected. The results obtained prove the inability of the isolated virus to replicate in the used mammalian cells.

To reveal possible pathogenic properties of the isolated virus, suckling mice were infected. It was shown that intracerebral infection with a dose of 105 TCID50/mouse did not cause any clinical manifestations of infection during the whole period of observation (21 days).

Nucleotide sequence screening of total RNA from infected C6/36 cells by next-generation sequencing (NGS) allowed us to identify a fragment of nucleotide sequence corresponding to ORF1 of the Dezidougou negevirus genome. The fragment was 471 bp in length with a read count of 1465 and a coverage of 293. Sanger sequencing was performed to determine the complete nucleotide sequence of DEZV negevirus. The genome is a non-segmented positive-sense single-stranded RNA 9010 nt in size, and has three open reading frames. The obtained sequence was deposited in the GenBank database under accession number: PP975071.1. The similarity of the nucleotide sequence of the isolated DEZV Yakutsk 2023 variant with known negevirus isolates is summarized in the following Table. The highest level of similarity (92%) in nucleotide sequence DEZV Yakutsk 2023 showed in comparison with the isolate from Coquillettidia richiardii from Germany (DEZV OP576003). The similarity rate in comparison with a DEZV variant isolated in Spain (MT096525) was 86%. The level of similarity with nucleotide sequences of other negeviruses was as follows: with Kustavi Negevirus (ON949944, Spain) – 69.6%, Utsjoki Negevirus 3 (ON955101, Finland) – 72.1%, Wallerfield virus (KX518839, Panama) and Uxmal virus (MH719095.1, Mexico) – 68%. The presence of a large number of amino acid substitutions indicates a significant genetic diversity of negeviruses.

Table. Levels of homology (%) of nucleotide/derived amino acid sequences of strain DEZV Yakutsk 2023 in comparison with the closest negevirus strains

Таблица. Уровни сходства (%) нуклеотидной/выведенной аминокислотной последовательностей штамма DEZV Yakutsk 2023 в сравнении с наиболее близкими штаммами негевирусов

Name of strain Название штамма | GenBank | Country Страна | Year Год | Nucleotide sequence, % Нуклеотидная последовательность, % | Amino acid sequence, % Аминокислотная последовательность, % |

Dezidougou virus strain 8345 | OP576003.1 | Germany Германия | 2014 | 91.95 | 98.40 |

Dezidougou virus strain ArA 20086 | JQ675604.1 | Côte d’Ivoire Кот-д’Ивуар | 1984 | 85.22 | 96.27 |

Dezidougou virus strain DEZI/ Aedes africanus/SEN/ DAK-AR-41524/1984 | KY968698.1 | Senegal Сенегал | 1984 | 86.24 | 96.18 |

Dezidougou virus isolate FTA2-3 | MT096525.1 | Spain Испания | 2015 | 86.08 | 96.44 |

Kustavi Negevirus isolate FIN/VS-2018/100 | ON949944.1 | Finland Финляндия | 2017 | 69.61 | 71.62 |

Agua Salud Negevirus isolate PA-2013-MP416-PP | MK959116.1 | Panama Панама | 2013 | 67.31 | 57.38 |

Wallerfield virus strain TR7904 | NC_023440.1 | Trinidad and Tobago Тринидад и Тобаго | 2009 | 67.84 | 61.27 |

Wallerfield virus isolate PA-2013-MP416-PP | MK959117.1 | Panama Панама | 2013 | 68.16 | 61.45 |

Uxmal virus isolate UXMV-M985 | MH719095.1 | Mexico Мексика | 2007 | 68.57 | 60.58 |

Utsjoki Negevirus 3 isolate FIN/L-2018/06 | ON955101.1 | Finland Финляндия | 2015 | 72.14 | 82.15 |

Culex Biggie-like virus strain CBigVL/Kern | MH188028.1 | USA США | 2016 | 70.88 | 55.19 |

Culex negev-like virus 3 strain mos172X44875 | NC_035129.1 | Australia Австралия | 2015 | 70.00 | 55.30 |

Tanay virus isolate 11-3, complete genome | KF425262.1 | Philippines Филиппины | 2005 | 70.02 | 52.82 |

Goutanap virus 16GH1 | LC504569.1 | Ghana Гана | 2016 | 68.85 | 56.00 |

Fig. 3 shows the phylogenetic tree with our isolated DEZV Yakutsk 2023 and negeviruses. The closest to DEZV Yakutsk 2023 is the prototypical Dezidougou virus strain 8345 (OP576003.1) from Germany with an identity level of 91.95%. Among other negeviruses, the closest are viruses isolated in Finland (Utsjoki Negevirus 1, ON949947), Castlerea virus in Australia (KX886280) and Ying Kou virus in China (isolate NC 040636.1) with a similarity level of 72.1‒72.4% in nucleotide sequences.

Fig. 3. Phylodendrogram showing the maximum likelihood analysis of full-length viral sequences of DEZV and viruses of the genus Negevirus.

The sequence characterized in this study is highlighted with the symbol (●). A, B, and C are the main branches of negeviruses.

Рис. 3. Филодендрограмма, отображающая анализ максимального правдоподобия полноразмерных вирусных последовательностей DEZV и других негевирусов.

Последовательность, охарактеризованная в этом исследовании, выделена символом (●). А, В и С ‒ основные ветви негевирусов.

Discussion

Over the past decades, a large number of insect viruses have been discovered that belong to various families, including viruses belonging to genus Negevirus.

The virus isolated by us from pools of mosquitoes sampled in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) replicated efficiently in C6/36 (Aedes albopictus) cells, causing their death. At the same time, it was unable to infect and multiply in mammalian cell cultures (Vero E6, HEK-293A and SPEV). The isolated virus did not cause pathologic manifestations in suckling mice when infected intracerebrally with a high dose. The results of complete genome sequencing determined that it belonged to negeviruses, the highest level of homology was noted with Dezidougou virus, first isolated in Côte d’Ivoire. Electron microscopic examination of purified virus suspension showed the presence of spherical viral particles with a diameter of 45‒55 nm, characteristic of negeviruses. In a number of studies about negeviruses, it has been shown that these viruses reproduce only in arthropod cells and do not replicate in vertebrate cells. Thus, in [6], the authors infected C6/36, Vero, and BHK-21 cell cultures, as well as newborn mice (intracerebral inoculation) with Negev (NEGV), Piura (PIUV), Dezidougou (DEZV), Ngewotan (NWTV), Loreto (LORV), and Santana (SANV) viruses. All of the above viruses were only able to replicate in C6/36 cells and did not cause any disease in sucklings, which is consistent with the results of the present study.

The genus Negevirus consists of a diverse group of insect-specific viruses, with a genome represented by single-stranded (+)RNA, isolated from mosquitoes and phlebotomine mosquitoes in Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Panama, USA, Germany, Spain and Nepal. These viruses were isolated from pools of mosquitoes collected in the field, suggesting that they are fairly widespread among mosquitoes in the wild. Most negeviruses are characterized by high genetic variability and the presence of interspecies transmission. Negeviruses are widely distributed geographically and have a diverse range of hosts among insects – mosquitoes of the genera Culex, Aedes and Anopheles, sand flies of the genus Lutzomyia, etc. [17, 18]. Our results on the isolation of DEZV in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) in Russia confirm the data on the wide geographical distribution of Negeviruses.

The biological and potential public health significance of negeviruses remains to be determined. Since negeviruses were originally isolated from naturally selected mosquitoes of different genera that are vectors of arboviruses, it is possible that negevirus infection may influence the susceptibility and vector competence of vectors to viral pathogens of vertebrates. For example, it has been shown experimentally on Ae. aegypti that infection of mosquitoes with certain strains of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia prevents dengue virus replication and reduces vector competence [18, 19]. And if a bacterial endosymbiont can alter mosquito vector competence to arboviruses, it is likely that a viral symbiont could also have a similar effect. It is thought that ISVs could also potentially be used as biological control agents with the proposed elimination of superinfection with human pathogenic arboviruses and maintenance of the effect in nature through transovarial transmission [20]. In a recent study, the negevirus Piura has been shown to effectively inhibit Zika virus replication in insect cells. Co-infection of C6/36 cells with PIUV resulted in a 10,000-fold reduction in the infectious titer of Zika virus compared to Zika virus mono-infected cells. At the same time, Zika virus was unable to inhibit PIUV replication [21]. E. Patterson et al. [22] demonstrated that Negev virus inhibited replication of Chikungunya arboviruses and Eastern equine encephalitis arboviruses belonging to the Alphavirus genus in coinfected mosquito cells. Other researchers have shown that insect-specific Culex Flavivirus (CxFV) Izabal did not inhibit West Nile virus (WNV) replication in C6/36 cells and Culex quinquefas ciatus mosquitoes. Most importantly, the WNV transmissible efficacy was enhanced in CxFV-infected mosquitoes [23].

It has previously been shown experimentally that negeviruses are found in the salivary glands of insects and, therefore, there is the potential for transmission to the vertebrate host during feeding [24, 25]. Consequently, humans and other vertebrates may have contact with negeviruses, increasing the likelihood of some of them adapting and eventually evolving already as a conditional vertebrate pathogen. There is a reasonable assumption that many vertebrate viruses transmitted by arthropods were originally insect-specific [7]. The assumption that ISVs are ancestors of arboviruses makes these viruses a potential tool for studying the evolution of host-to-host transmission.

Conclusion

For the first time in the territory of the Russian Federation, a virus of genus Negevirus was identified and isolated in a pool of mosquitoes sampled in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). The isolated negevirus strain DEZV Yakutsk 2023 replicated efficiently in C6/36 cells (Ae. albopictus), causing their death. At the same time, it was unable to infect and multiply in the mammalian cell cultures used and did not cause pathologic manifestations in suckling mice upon intracerebral infection. The complete nucleotide sequence of the viral genome of DEZV Yakutsk 2023 was determined by NGS and Sanger sequencing and phylogenetic analysis was performed.

Further research on the prevalence of negeviruses, their virological features, potential public health significance and impact on vector competence seems to be important and promising.

About the authors

Marina A. Stepanyuk

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: stepanyuk_ma@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0009-0002-2658-7746

junior researcher of the department of molecular virology of flaviviruses and viral hepatitis

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionStanislav S. Legostaev

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: legostaev_ss@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6202-445X

trainee researcher of the department of molecular virology of flaviviruses and viral hepatitis

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionKristina V. Karelina

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: karelina_kv@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0009-0003-1421-1765

trainee researcher of the department of molecular virology of flaviviruses and viral hepatitis

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionNina F. Timofeeva

M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University

Email: niakswan@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9895-5873

Researcher

Russian Federation, 677000, Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), YakutskKsenia F. Emtsova

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: k.emtsova@g.nsu.ru

ORCID iD: 0009-0003-5165-5357

trainee researcher of microscopic research department

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionOlesia V. Ohlopkova

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Author for correspondence.

Email: ohlopkova_ov@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-8214-7828

Candidate of Biological Sciences, Senior Researcher, Department of Biophysics and Environmental Research

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionOleg S. Taranov

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: taranov@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6746-8092

head of microscopic research department

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionVladimir A. Ternovoi

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: tern@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1275-171X

Candidate of Biological Sciences, Leading Researcher, Department of Molecular Virology of Flaviviruses and Viral Hepatitis

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionAlbert V. Protopopov

M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University

Email: a.protopopov@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6543-4596

Doctor of Biological Sciences, Chief Researcher

Russian Federation, 677000, Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), YakutskValery B. Loktev

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: loktev@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-0229-321X

MD, PhD, DSc, Prof., academician RANS, Chief Researcher, Department of Molecular Virology of Flaviviruses and Viral Hepatitis

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionVictor A. Svyatchenko

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: svyat@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2729-0592

Candidate of Biological Sciences, Leading Researcher, Department of Molecular Virology of Flaviviruses and Viral Hepatitis

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionAlexander P. Agafonov

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector»

Email: agafonov@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2577-0434

Doctor of Biological Sciences, Director General, Federal Biotechnology and Biotechnology

Russian Federation, 630559, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk regionReferences

- Kuno G. A survey of the relationships among the viruses not considered arboviruses, vertebrates, and arthropods. Acta Virol. 2004; 48(3): 135–44.

- Calzolari M., Zé-Zé L., Vázquez A., Sánchez Seco MP., Amaro F., Dottori M. Insect-specific flaviviruses, a worldwide widespread group of viruses only detected in insects. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016; 40: 381–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2015.07.032

- Roundy CM., Azar SR., Rossi SL., Weaver SC., Vasilakis N. Insect-specific viruses: a historical overview and recent developments. Adv. Virus Res. 2017; 98: 119–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.10.001

- Blitvich B.J., Firth A.E. Insect-specific flaviviruses: a systematic review of their discovery, host range, mode of transmission, superinfection exclusion potential and genomic organization. Viruses. 2015; 7(4): 1927–59. https://doi.org/doi: 10.3390/v7041927

- Carvalho V.L., Long M.T. Insect-specific viruses: an overview and their relationship to arboviruses of concern to humans and animals. Virology. 2021; 557: 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2021.01.007

- Vasilakis N., Forrester N.L., Palacios G., Nasar F., Savji N., Rossi SL., et al. Negevirus: a proposed new taxon of insect-specific viruses with wide geographic distribution. J. Virol. 2013; 87(5): 2475–88. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00776-12

- Nunes M.R.T., Contreras-Gutierrez M.A., Guzman H., Martins L.C., Barbirato M.F., Savit C., et al. Genetic characterization, molecular epidemiology, and phylogenetic relationships of insect-specific viruses in the taxon Negevirus. Virology. 2017; 504: 152–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2017.01.022

- Auguste A.J., Carrington C.V.F., Forrester N.L., Popov V.L., Guzman H., Widen S.G., et al. Characterization of a novel Negevirus and a novel Bunyavirus isolated from Culex (Culex) declarator mosquitoes in Trinidad. J. Gen. Virol. 2014; 95(Pt. 2): 481–5. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.058412-0

- Truong Nguyen P.T., Culverwell C.L., Suvanto M.T., Korhonen E.M., Uusitalo R., Vapalahti O., et al. Characterisation of the RNA virome of nine Ochlerotatus species in Finland. Viruses. 2022; 14(7): 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14071489

- da Silva Ribeiro A.C., Martins L.C., da Silva S.P., de Almeida Medeiros D.B., Miranda K.K.P., Nunes Neto J.P., et al. Negeviruses isolated from mosquitoes in the Brazilian Amazon. Virol. J. 2022; 19(1): 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01743-z

- Hermanns K., Marklewitz M., Zirkel F., Overheul G.J., Page R.A., Loaiza J.R., et al. Agua Salud alphavirus defines a novel lineage of insect-specific alphaviruses discovered in the New World. J. Gen. Virol. 2020; 101(1): 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001344

- Auguste A.J., Langsjoen R.M., Porier D.L., Erasmus J.H., Bergren N.A., Bolling B.G., et al. Isolation of a novel insect-specific flavivirus with immunomodulatory effects in vertebrate systems. Virology. 2021; 562: 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2021.07.004

- Svyatchenko V., Nikonov S., Mayorov A., Gelfond M., Loktev V. Antiviral photodynamic therapy: Inactivation and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro using methylene blue and Radachlorin. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021; 33: 102112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102112

- Toth K., Spencer J., Dhar D., Sagartz J., Buller R., Painter G., et al. Hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir, CMX001, prevents adenovirus induced mortality in a permissive, immunosuppressed animal model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008; 105(20): 7293–97. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0800200105

- Lei C., Yang J., Hu J., Sun X. On the calculation of TCID 50 for quantitation of virus infectivity. Virol. Sin. 2021; 36(1): 141–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-020-00230-5

- Rodgers MA., Wilkinson E., Vallari A., McArthur C., Sthreshley L., Brennan CA., et al. Sensitive next-generation sequencing method reveals deep genetic diversity of HIV-1 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Virol. 2017; 91(6): e01841-16. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01841-16

- Walker T., Jeffries C.L., Mansfield K.L., Johnson N. Mosquito cell lines: history, isolation, availability and application to assess the threat of arboviral transmission in the United Kingdom. Parasit. Vectors. 2014; 7: 382. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-382

- Müller G., Schlein Y. Plant tissues: the frugal diet of mosquitoes in adverse conditions. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2005; 19(4): 413–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2005.00590.x

- Moreira L.A., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., Jeffery J.A., Lu G., Pyke A.T., Hedges L.M., et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009; 139(7): 1268–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042

- Öhlund P., Lundén H., Blomström A.L. Insect-specific virus evolution and potential effects on vector competence. Virus Genes. 2019; 55(2): 127–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-018-01629-9

- Carvalho V.L., Prakoso D., Schwarz E.R., Logan T.D., Nunes B.T.D., Beachboard S.E., et al. Negevirus Piura suppresses Zika virus replication in mosquito cells. Viruses. 2024; 16(3): 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16030350

- Patterson EI., Kautz TF., Contreras-Gutierrez MA., Guzman H., Tesh RB., Hughes GL. Negeviruses reduce replication of alphaviruses during coinfection. J. Virol. 2021; 95(14): e0043321. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00433-21

- Kent R.J., Crabtree M.B., Miller B.R. Transmission of West Nile virus by Culex quinquefasciatus say infected with Culex Flavivirus Izabal. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010; 4(5): e671. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000671

- Higgs S., Beaty B.J. Natural cycles of vector-borne pathogens. In: Marquardt M.C., ed. Biology of Disease Vectors. New York: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005: 167–85.

- Guerrero D., Cantaert T., Missé D. Aedes mosquito salivary components and their effect on the immune response to arboviruses. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020; 10: 407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00407

Supplementary files