Вирус Зика в тени: недооцененный фактор в эпидемиологии лихорадочных заболеваний в Нигерии

- Авторы: Agbajelola V.I.1,2, Oluwadare F.A.1, Hamman M.M.2, Lateef A.M.2

-

Учреждения:

- Университет Ибадана

- Университет Миссури

- Выпуск: Том 70, № 4 (2025)

- Страницы: 317-323

- Раздел: ОБЗОРЫ

- URL: https://virusjour.crie.ru/jour/article/view/16769

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.36233/0507-4088-328

- EDN: https://elibrary.ru/bimlfa

- ID: 16769

Цитировать

Полный текст

Аннотация

Предпосылки. Передаваемый комарами вирус Зика (Orthoflavivirus zikaense), представитель семейства Flaviviridae рода Orthoflavivirus, привлекает международное внимание из-за своих неврологических и врожденных последствий. Хотя вирус является эндемичным для Африки, его распространенность в Нигерии остается малоизученной и часто маскируется другими лихорадочными заболеваниями, такими как малярия и лихорадка денге. В настоящем обзоре обобщены данные исследований, опубликованных в рецензируемых журналах в период с 2015 по 2025 г., с целью анализа эпидемиологических особенностей, диагностических трудностей и значения для общественного здравоохранения инфекции, вызываемой вирусом Зика, в Нигерии.

Материалы и методы. Был проведен нарративный синтез исследований, сообщающих о случаях заражения вирусом Зика в Нигерии, с использованием целенаправленного поиска в базах данных PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science и African Journals Online. Включали рецензируемые статьи на английском языке, содержащие серологические или молекулярные данные, полученные при исследованиях в популяциях людей или переносчиков вирусов.

Результаты. Данные 11 исследований в 10 штатах показывают, что серопревалентность вируса Зика варьирует от 1,4% до более чем 50%, особенно среди беременных женщин и пациентов с лихорадочными состояниями. Диагностические пробелы, связанные со схожестью симптомов и серологической перекрестной реактивностью, способствуют недооценке распространенности вируса. Коциркуляция с другими арбовирусами и ограниченный охват эпидемиологическим надзором дополнительно затрудняют оценку бремени вируса Зика на общественное здоровье.

Заключение. Вирус Зика, вероятно, циркулирует в Нигерии скрытно, чему способствуют экологические и инфраструктурные факторы. Несистематический контроль за переносчиками, ограниченные возможности диагностики и отсутствие интегрированного надзора за арбовирусами мешают своевременному выявлению инфекции. Опыт борьбы с другими вирусами, передающимися комарами рода Aedes, должен лечь в основу унифицированной и активной национальной стратегии борьбы с инфекцией, вызываемой вирусом Зика.

Ключевые слова

Полный текст

Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV), now taxonomically classified as Orthoflavivirus zikaense under the genus Orthoflavivirus and family Flaviviridae following ICTV ratification in April 2023, is a mosquito-borne virus that has gained global notoriety due to its strong association with severe neurological and congenital disorders, notably Guillain–Barré syndrome and microcephaly in newborns [1, 2]. The virus was first isolated in 1947 from a rhesus monkey in Uganda’s Zika Forest and was initially considered of limited clinical relevance. However, it is now recognized as a serious public health threat due to its diverse transmission routes and potential for large outbreaks. ZIKV is primarily transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, mosquitoes well-adapted to tropical and subtropical urban environments [3]. Additionally, non-vector modes of transmission such as vertical transmission during pregnancy, sexual transmission, and via blood transfusions and organ transplants contribute to its epidemiological complexity [4]. Although most infections are asymptomatic or present with mild symptoms like fever, rash, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia, the virus’s potential for causing debilitating outcomes in specific populations warrants serious concern.

The global burden of ZIKV was exemplified during the explosive outbreak in the Americas between 2015 and 2016. During this period, the rise in congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) and neurological complications led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare ZIKV a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in February 2016 [5]. Brazil, the epicenter of the outbreak, reported over 200,000 suspected cases and more than 2,000 confirmed cases of microcephaly by late 2016, illustrating the virus’s profound clinical and socioeconomic impacts [5]. In several affected countries, the outbreaks overwhelmed healthcare systems, exposed gaps in diagnostic infrastructure, and highlighted the fragility of surveillance mechanisms in low- and middle-income settings.

Despite ZIKV’s African origin, its early history on the continent, including Nigeria, has been characterized by sparse and inconsistent surveillance. In Nigeria, ZIKV was first detected in humans in the late 1970s [6]. However, epidemiological interest in the virus has since remained limited, and few systematic efforts have been made to monitor its prevalence or transmission patterns. This neglect is particularly concerning given that Nigeria harbors dense human populations and a widespread presence of competent Aedes vectors, especially in urban and peri-urban areas [7]. These ecological and demographic conditions are highly favorable to arboviral transmission, yet ZIKV continues to be eclipsed by more well-recognized arboviruses such as dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya.

The overlapping clinical presentations of ZIKV with other endemic febrile illnesses, such as malaria, typhoid fever, and dengue further contribute to its diagnostic obscurity. Most patients with ZIKV are misclassified due to non-specific symptoms and low clinical suspicion. Furthermore, laboratory diagnosis is challenged by the serological cross-reactivity of ZIKV antibodies with other flaviviruses, compounded by the limited availability of molecular diagnostic platforms and trained personnel [8]. These factors contribute to a persistent underreporting and misdiagnosis of ZIKV cases, particularly in pregnant women and febrile individuals who are most at risk of adverse outcomes.

Adding to these challenges is the broader context of Nigeria’s under-resourced healthcare infrastructure. Fragmented vector control programs, inadequate antenatal care utilization, and presumptive treatment of febrile illnesses without confirmatory testing hinder the early identification and management of ZIKV infections. Pregnant women may present late to healthcare facilities or not at all, while febrile patients are frequently treated empirically for malaria or typhoid without laboratory confirmation. These realities suggest that ZIKV may be circulating silently in the population, representing an underrecognized contributor to Nigeria’s febrile disease burden.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of peer-reviewed literature on Zika virus in Nigeria, published between 2015 and 2025. Specifically, it focuses on the epidemiology of ZIKV in pregnant women and febrile populations, identifies existing diagnostic and surveillance gaps, and contextualizes the findings within the broader framework of arboviral disease control in Nigeria. By doing so, the review highlights the need for greater clinical awareness, enhanced vector control, and investment in diagnostic infrastructure to ensure ZIKV does not continue to remain in the shadows of Nigeria’s public health priorities.

This review employed a narrative synthesis approach to summarize current knowledge on ZIKV in Nigeria. A structured and targeted literature search was conducted across major scientific databases including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and African Journals Online (AJOL). The search focused on articles published between 2015 and 2025 and used combinations of relevant keywords such as «Zika virus», «Nigeria», «seroprevalence», «Aedes mosquitoes», and «arbovirus», connected using Boolean operators. Eligible studies were required to be peer-reviewed, published in English, and report original data on ZIKV infections in humans or vectors specific to Nigeria. Given the narrative nature of the review, no formal risk-of-bias assessment tool was employed, but careful attention was given to the methodological quality and relevance of each included study. Where applicable, visualization was created using R software (version 4.3.0), specifically leveraging packages such as ggplot2 to facilitate clear presentation of data trends and patterns [9].

Epidemiology of Zika Virus in Nigeria (2015–2025)

Although ZIKV has likely circulated in Nigeria for decades, epidemiological data only began to emerge meaningfully in the past ten years. A growing number of hospital-based and population-level studies conducted between 2015 and 2025 have reported serological and, to a lesser extent, molecular evidence of ZIKV infection across at least ten states spanning five geopolitical zones. Despite the expanding body of evidence, the true burden of ZIKV in Nigeria remains unclear due to underdiagnosis, non-specific clinical symptoms, and the absence of routine surveillance.

The reviewed studies, summarized in Table, predominantly employed cross-sectional designs targeting pregnant women, febrile patients, blood donors, and general outpatient populations. Reported prevalence estimates vary from 3.45 to 55.6% depending on the population studied, geographic location, and diagnostic methods used, while the overall prevalence estimates of ZIKV in Nigeria is 13.69% (95% CI: 12.7–14.75%). Notably, several studies reported both IgM and IgG antibody positivity, indicating ongoing and past infections, while a few employed RT-qPCR to confirm active viremia. Pregnant women emerged as a particularly vulnerable group, with some studies revealing double-digit IgM antibody prevalence and a small proportion testing PCR-positive, evidence suggestive of recent transmission and the potential risk of congenital Zika syndrome.

Table. Summary of reported studies on Zika virus in Nigeria (2015–2025)

Таблица. Перечень опубликованных исследований по вирусу Зика в Нигерии (2015–2025 гг.)

S/N № п/п | References Ссылки | Study design Дизайн исследования | Population studied Изучаемая популяция | Diagnostic Techniques Диагностические методы | State Штат | Positive cases Положительные случаи | Prev (%) Превалентность (%) | Total samples Общее количество образцов |

1 | [10] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Outpatients, blood donors (incl. pregnant, HIV+) Амбулаторные пациенты, доноры крови (вкл. беременных, ВИЧ+) | RecomLine Tropical Fever immunoblot for ZIKV IgG (NS1 & Equad) Иммуно-блот RecomLine Tropical Fever на ZIKV IgG (NS1 и Equad) | Nasarawa (Central), Abia (South), Kaduna (North) Насарава (Центр), Абия (Юг), Кадуна (Север) | 167 | 19.2 | 871 |

2 | [11] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Hospital patients Госпитализированные пациенты | ELISA (IgM, IgG), malaria RDT ИФА (IgM, IgG), экспресс-тест на малярию | Kaduna Кадуна | 61 | 14.5 | 420 |

3 | [12] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Pregnant women attending antenatal care Беременные женщины, посещающие дородовой прием | MAC-ELISA for ZIKV IgM, followed by RT-qPCR confirmation MAC ИФА на ZIKV IgM, подтверждение методом RT-qPCR | Zaria, Kaduna State (North-West Nigeria) Зария, штат Кадуна (Северо-Запад Нигерии) | 53 | 29.4 | 180 |

4 | [13] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Pregnant women Беременные женщины | ELISA and microneutralization test (MNT) ИФА и микронейтрализационный тест (MNT) | Gombe Гомбе | 53 | 26.5 | 200 |

5 | [14] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Pregnant women Беременные женщины | ELISA IgM/IgG + HI test ИФА IgM/IgG + тест торможения гемагглютинации (HI) | Oyo Ойо | 20 | 55.6 | 36 |

6 | [15] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Pregnant women Беременные женщины | ELISA + PCR ИФА + ПЦР | Kwara state Квара | 32 | 16.0 | 200 |

7 | [16] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Pregnant women Беременные женщины | Zika virus IgG and IgM capture Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ИФА тест на Zika IgG и IgM | Lagos state Лагос | 12 | 3.4 | 352 |

8 | [17] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Pregnant women Беременные женщины | Commercial sandwich enzyme-linked ELISA- (ZV-IgG) Коммерческий сэндвич-ИФА тест на ZV-IgG | Plateau Плато | 13 | 14.4 | 90 |

9 | [18] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Febrile patients ≥ 1 year Пациенты с лихорадкой ≥ 1 года | Lateral-flow IgM/IgG test Латерально-потоковый тест IgM/IgG | Cross River State Кросс-Ривер | 12 | 12 | 100 |

10 | [19] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Mixed outpatients (~ 60% pregnant women) at six healthcare facilities Смешанные амбулаторные пациенты (~ 60% беременные) в шести медучреждениях | ZIKV NS1-based ELISA (IgM, IgG); confirmatory neutralization assay; subset RT-PCR ИФА на NS1 ZIKV (IgM, IgG); подтверждающий нейтрализационный тест; RT-PCR подгруппа | North Central Nigeria (6 facilities) Северная Центральная Нигерия (6 учреждений) | 48 | 10 | 468 |

11 | [20] | Prospective cohort Проспективная когорта | Pregnant women Беременные женщины | Rapid IgM/IgG test, confirmatory ELISA + Neutralization Быстрый тест IgM/IgG, подтверждающий ИФА + нейтрализация | Plateau Плато | 38 | 3.8 | 1006 |

12 | [21] | Cross-sectional Поперечное | Females of childbearing age Женщины репродуктивного возраста | ELISA + PCR ИФА + ПЦР | Niger & Nasarawa Нигер и Насарава | 83 | 20.8 | 400 |

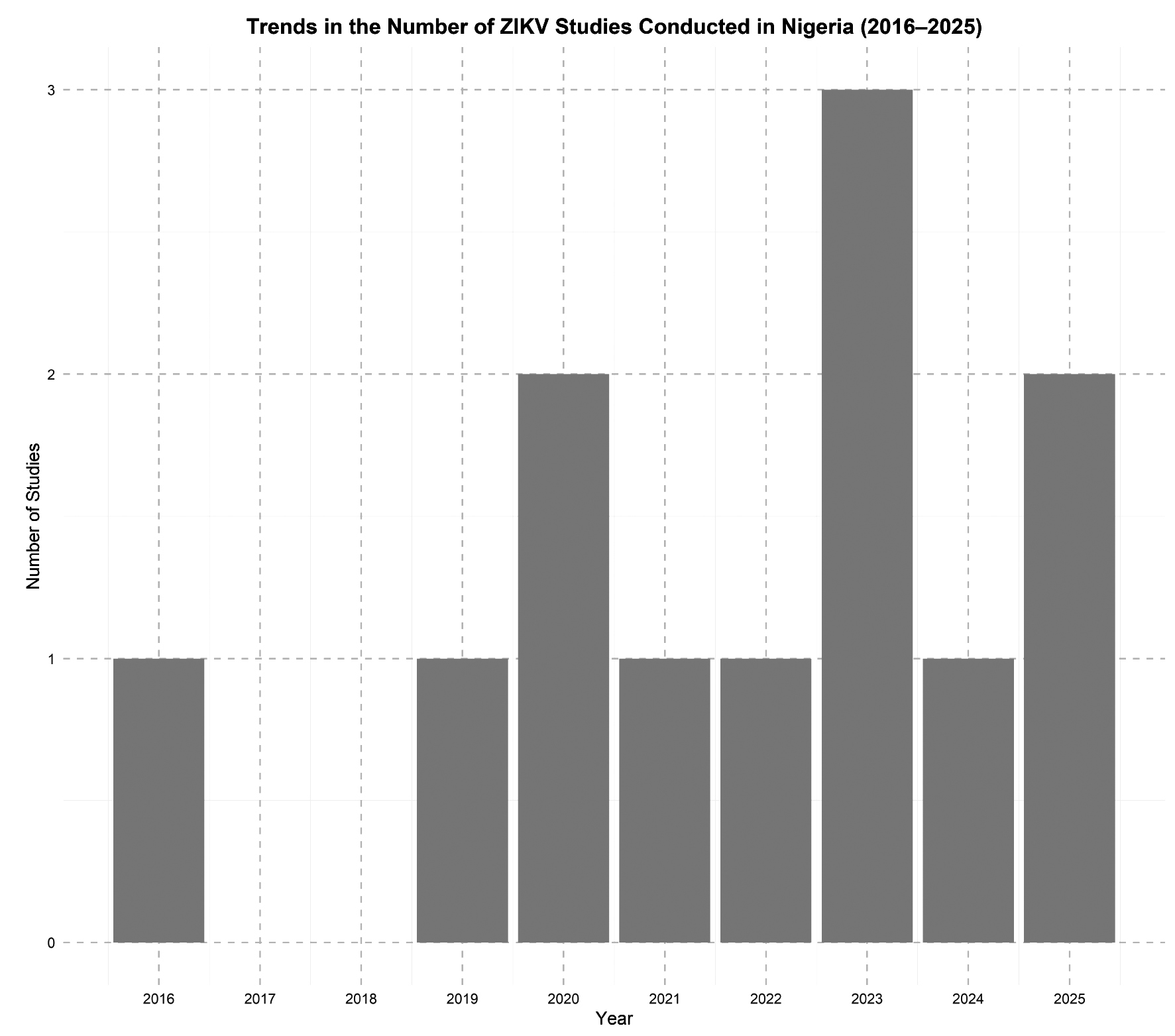

Geographical differences in ZIKV exposure were evident, potentially reflecting variations in vector distribution, urbanization, healthcare access, and diagnostic capacity. Among febrile patients, ZIKV was also detected at moderate rates, raising concerns about its under recognition in clinical settings where malaria and typhoid are more commonly suspected. However, interpretation of seroprevalence findings must be approached cautiously, as many studies relied on serological assays prone to cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses, such as dengue and yellow fever, which are endemic in Nigeria. As shown in Figure, the number of ZIKV-related studies in Nigeria has gradually increased over the last decade, with notable peaks in 2023, reflecting a growing but still limited research focus on the virus. Overall, while the evidence base remains limited, available studies suggest that ZIKV is circulating in Nigeria, albeit under the radar and may be contributing to the broader landscape of undiagnosed febrile illnesses.

Figure. Trends in Number of studies conducted on ZIKV in Nigeria in the last decade

Рисунок. Динамика количества исследований, посвященных вирусу Зика в Нигерии за последнее десятилетие

These findings collectively indicate that ZIKV is not only present but likely underreported in Nigeria, and it is detection among pregnant women and febrile patients highlights its clinical and epidemiological relevance, particularly in regions where arboviral surveillance is weak or non-existent. Yet, ZIKV has remained in the shadows of more frequently diagnosed infections such as dengue, malaria, and yellow fever. Meanwhile, the lack of community-based surveillance studies also limits our understanding of asymptomatic and rural infections, and most current data are derived from health facilities, which may not adequately capture infections in populations with limited access to care.

Overlapping Burdens and Diagnostic Blind Spots

ZIKV exists within a complex web of overlapping infectious diseases in Nigeria, particularly in regions burdened by co-circulating arboviruses and other febrile pathogens, and while it gained international attention primarily due to its teratogenic effects in pregnancy, emerging evidence from Nigeria suggests that its impact may extend well beyond this high-risk group, because febrile individuals (who may be harboring ZIKV infections) might be often misdiagnosed or treated presumptively for malaria or typhoid in clinical practice.

One of the major challenges in detecting ZIKV stems from its nonspecific clinical presentation, which mimics common endemic illnesses such as malaria, dengue, and typhoid fever. In regions with high malaria transmission, febrile illnesses are frequently attributed to Plasmodium falciparum without laboratory confirmation, effectively excluding ZIKV and other arboviruses from clinical consideration [22, 23]. This problem is further amplified in co-infected individuals, where overlapping symptoms such as fever, rash, and joint pain blur the clinical picture, increasing the likelihood of missed or delayed ZIKV diagnoses [24].

Ecological and entomological factors also contribute to this diagnostic blind spot. ZIKV shares vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, with other arboviruses such as dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus (YFV), and chikungunya. These vectors thrive in urban and peri-urban areas where water storage practices, poor drainage systems, and dense human populations create ideal breeding environments [24]. The co-circulation of multiple arboviruses within the same ecological and geographical settings increases the likelihood of misdiagnosis and underreporting, especially during outbreaks categorized as “fevers of unknown origin.”

Despite the known presence of competent Aedes vectors in Nigeria for decades, vector control efforts remain fragmented, largely reactive, and poorly integrated into broader disease prevention strategies [22, 25]. Factors such as rapid urbanization, poor sanitation infrastructure, and lack of sustained vector surveillance contribute to persistent arbovirus transmission, including ZIKV. These structural challenges disproportionately affect underserved populations, where access to healthcare, laboratory diagnostics, and vector control measures is already limited [26, 27].

Adding to the problem is the reliance on hospital-based studies for ZIKV surveillance in Nigeria. Most existing data focus on symptomatic individuals who present at healthcare facilities, primarily pregnant women and febrile patients. Consequently, there is a significant knowledge gap regarding asymptomatic or subclinical ZIKV infections, which may constitute a substantial proportion of total cases. Without community-based surveillance systems or routine integration of ZIKV testing into diagnostic panels for febrile illnesses, a large segment of the infected population remains invisible in national health data.

Addressing these diagnostic blind spots will require a multi-pronged approach, including enhanced clinical awareness, improved access to molecular and serological diagnostics, integration of ZIKV into differential diagnosis protocols, and expansion of surveillance beyond healthcare settings to include communities and high-risk populations.

Leveraging Arboviral Overlaps for Improved Zika Virus Control in Nigeria

The overlapping ecology, symptomatology, and transmission pathways of Aedes-borne arboviruses, such as Zika virus (ZIKV), dengue virus (DENV), chikungunya virus, and yellow fever virus (YFV) pose unique challenges for Nigeria’s public health response. However, these overlaps also offer critical opportunities to develop integrated and more efficient control strategies, even though Nigeria’s response to arboviruses has always been fragmented and largely reactive. The growing body of evidence on ZIKV circulation provides a chance to strengthen broader arboviral surveillance and vector control frameworks.

Experiences from past arboviral outbreaks in Nigeria highlight the urgency of adopting a comprehensive approach to control. Despite the availability of vaccines, diseases like yellow fever continue to cause periodic and deadly outbreaks, such as the 2020 episode in Delta State, which had a case fatality rate of 62.5% [28]. Similarly, the recent emergence of novel dengue virus genotypes in Lagos, affecting both pediatric and geriatric populations, points to ongoing silent transmission in urban areas [29]. These examples underscore the limitations of relying solely on vaccination, especially for arboviruses like ZIKV, for which no vaccine currently exists. Therefore, Nigeria must prioritize integrated and collaborative strategies for arboviral control, focusing on surveillance, vector management, and community engagement to prevent future outbreaks.

Importantly, the shared Aedes mosquito vector means that interventions aimed at controlling one virus can have broader benefits, therefore, coordinated efforts in entomological surveillance, such as monitoring vector density, breeding patterns, and insecticide resistance should be prioritized across arboviruses, and not just for ZIKV. Improving diagnostic capacity is equally essential, because the current lack of routine ZIKV testing, particularly in febrile and pregnant populations, limits the country’s ability to detect and respond to outbreaks. Introducing ZIKV diagnostics into the standard panel for febrile illnesses and maternal health care would also facilitate early identification and response.

Strategically, ZIKV control in Nigeria should not be pursued in isolation. Instead, it should be embedded within an integrated arboviral response system that promotes intersectoral collaboration among public health authorities, environmental agencies, researchers, and urban planners. Real-time data sharing, early warning systems, and the development of national guidelines for arboviral disease management will help bridge current gaps.

Conclusion

ZIKV remains a largely overlooked but potentially significant contributor to Nigeria’s febrile disease burden. Despite its likely silent circulation across various regions of the country, limited awareness, overlapping symptomatology with other endemic diseases, and inadequate diagnostic infrastructure have kept ZIKV in the shadows. The evidence synthesized in this review highlights sporadic yet concerning serological and molecular findings, particularly among pregnant women and febrile individuals, underscoring both the epidemiological reality of the virus and the systemic failures to recognize its presence. Nigeria’s public health response to arboviruses has historically been reactive and disease specific. However, the ecological and clinical overlaps between ZIKV, dengue, chikungunya, and yellow fever present an opportunity for integrated surveillance and control. The experiences from recent Aedes-borne outbreaks in Nigeria reinforce the need for stronger health system preparedness, sustainable vector control, and diagnostic innovation.

Об авторах

Victor Ibukun Agbajelola

Университет Ибадана; Университет Миссури

Автор, ответственный за переписку.

Email: agbajelolavictor@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-7289-7764

кафедра ветеринарной паразитологии, Университет Ибадана; кафедра ветеринарной патобиологии, Университет Миссури

Нигерия, штат Ойо; Колумбия, штат Миссури, 65211, СШАFranklyn Ayomide Oluwadare

Университет Ибадана

Email: aoluwadare292@stu.ui.edu.ng

ORCID iD: 0009-0009-0134-7130

Программа производства и контроля качества вакцин, Институт наук о жизни и Земле Панафриканского университета, включая здравоохранение и сельское хозяйство – PAULESI

Нигерия, штат ОйоMark Musa Hamman

Университет Миссури

Email: mhgkv@missouri.edu

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2237-6813

Кафедра ветеринарной патобиологии

США, Колумбия, штат Миссури, 65211Adeola Mariam Lateef

Университет Миссури

Email: amorff@missouri.edu

ORCID iD: 0009-0000-9710-740X

Кафедра ветеринарной патобиологии

США, Колумбия, штат Миссури, 65211Список литературы

- Postler T.S., Beer M., Blitvich B.J., Bukh J., de Lamballerie X., Drexler J.F., et al. Renaming of the genus Flavivirus to Orthoflavivirus and extension of binomial species names within the family Flaviviridae. Arch. Virol. 2023; 168(9): 224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-023-05835-1

- de Araújo T.V.B., Rodrigues L.C., de Alencar Ximenes R.A., de Barros Miranda-Filho D., Montarroyos U.R., de Melo A.P.L., et al. Association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly in Brazil, January to May, 2016: preliminary report of a case-control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016; 16(12): 1356–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30318-8

- Musso D., Gubler D.J. Zika virus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016; 29(3): 487–524. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00072-15

- Petersen L.R., Jamieson D.J., Powers A.M., Honein M.A. Zika virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016; 374(16): 1552–63. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1602113

- WHO. WHO statement on the first meeting of the International Health Regulations – 2005 (IHR 2005) Emergency Committee on Zika virus and observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations. Retrieved from WHO statement on the first meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR 2005) Emergency Committee on Zika virus and observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations; 2016.

- Fagbami A.H. Zika virus infections in Nigeria: virological and seroepidemiological investigations in Oyo State. J. Hyg. (Lond). 1979; 83(2): 213–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022172400025997

- Omatola C.A., Onoja B.A., Olayemi A., Eze A.A. Low seroprevalence of Zika virus infection among pregnant women in North-Central Nigeria. BMC Infec. Dis. 2021; 21(1): 403. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06073-1

- Olusola B.A., Bello M.B., Olaleye D.O. Seroprevalence of Zika virus among febrile patients in Nigeria: Implications for clinical diagnosis and public health. J. Infect. Pub. Health. 2021; 14(5): 656–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.11.006

- Wickham H., Chang W., Henry L., Pedersen T.L., Takahashi K., Wilke C., et al. GGPLOT2: create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics (R package version 3.3.5); 2019. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=ggplot2

- Mac P.A., Kroeger A., Daehne T., Anyaike C., Velayudhan R., Panning M. Zika, flavivirus and malaria antibody cocirculation in Nigeria. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023; 8(3): 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8030171

- Atai R.B., Aminu M., Ella E.E., Kia G.S.N., Obishakin E.T., Luka H.G., et al. Zika virus in Malaria-endemic populations: a climate change-driven syndemic in the Sudan savannah, Nigeria. Microbiol. Res. 2025; 16(6): 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16060109

- Adekola H.A., Ojo D.A., Balogun S.A., Dipeolu M.A., Mohammed M., Adejo D.S., et al. The prevalence of IgM antibodies to Zika virus in pregnant women in Northern Nigeria. Vopr. Virusol. 2023; 68(2): 117–23. https://doi.org/10.36233/0507-4088-162

- Bamidele O.S., Bakoji A., Yaga S.J., Ijaya K., Mohammed B., Yuguda I.Y., et al. Zika virus infections and associated risk factors among pregnant women in Gombe, Nigeria. Virol. Sin. 2025; 40(1): 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2024.12.008

- Oluwole T., Fowotade A., Mirchandani D., Almeida S., Plante K.S., Weaver S., et al. Seroprevalence of some arboviruses among pregnant women in Ibadan, Southwestern, Nigeria. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022; 116: S1–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.307

- Kolawole O.M., Suleiman M.M., Bamidele E.P. Molecular epidemiology of Zika virus and Rubella virus in pregnant women attending Sobi Specialist Hospital Ilorin, Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2020; 8(6): 2275–83. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20202234

- Shaibu J.O., Okwuraiwe A.P., Jakkari A., Dennis A., Akinyemi K.O., Li J., et al. Sero-molecular prevalence of Zika virus among pregnant women attending some public hospitals in Lagos State, Nigeria. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci. 2021; 3(5): 77–82. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejmed.2021.3.5.1075

- Anejo-Okopi J., Gotom D.Y., Chiehiura N.A., Okojokwu J.O., Amanyi D.O., Egbere J.O., et al. The seroprevalence of Zika virus infection among HIV positive and HIV negative pregnant women in Jos, Nigeria. Hosts Viruses 2020; 7(6): 129–36. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.hv/2020/7.6.129.136

- Otu A.A., Udoh U.A., Ita O.I., Hicks J.P., Ukpeh I., Walley J. Prevalence of Zika and malaria in patients with fever in secondary healthcare facilities in south-eastern Nigeria. Trop. Doct. 2019; 50(1): 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049475519872580

- Mathé P., Egah D.Z., Müller J.A., Shehu N.Y., Obishakin E.T., Shwe D.D., et al. Low Zika virus seroprevalence among pregnant women in North Central Nigeria, 2016. J. Clin. Virol. 2018; 105: 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2018.05.011

- Ogwuche J., Chang C.A., Ige O., Sagay A.S., Chaplin B., Kahansim M.L., et al. Arbovirus surveillance in pregnant women in north-central Nigeria, 2019–2022. J. Clin. Virol. 2023; 169: 105616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2023.105616

- Suleiman M.M., Kolawole O.M. Simultaneous detection and genomic characterization of Zika virus Protein M, E and NS1 using optimized primers from Asian and African Lineage. Vacunas. 2024; 25(1): 40–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacune.2024.02.008

- Adeleke M.A., Mafiana C.F., Idowu A.B., Adekunle M.F., Sam-Wobo S.O. Mosquito larval habitats and public health implications in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Tanzan J. Health Res. 2008; 10(2): 103–7. https://doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v10i2.14348

- Chimaeze C.O., Chukwuemeka N.A., Okechukwu N.E., Ayorinde D.F., Chukwubuofu N.U., Ogbonnaya O.C. Diversity and distribution of Aedes mosquitoes in Nigeria. New York Sci. J. 2018; 11(2): 50–7. https://doi.org/10.7537/marsnys110218.07

- Afolabi O.J., Simon-Oke I.A., Osomo B.O. Distribution, abundance and diversity of mosquitoes in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. J. Virol. Vect. Biol. 2013; 5(10): 132–6. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPVB2013.0133

- Ma J., Guo Y., Gao J., Tang H., Xu K., Liu Q., et al. Climate change drives the transmission and spread of vector-borne diseases: an ecological perspective. Biology (Basel). 2022; 11(11): 1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11111628

- Wilder-Smith A., Gubler D.J., Weaver S.C., Monath T.P., Heymann D.L., Scott T.W. Epidemic arboviral diseases: priorities for research and public health. Lancet. Infect Dis. 2017; 17(3): e101–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30518-7

- Otu A., Ebenso B., Etokidem A., Chukwuekezie O. Dengue fever – an update review and implications for Nigeria, and similar countries. Afr. Health Sci. 2019; 19(2): 2000–7. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v19i2.23

- WHO. Yellow fever – Nigeria; 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON336

- Kolawole O.M., Seriki A.A., Irekeola A.A., Bello K.E., Adeyemi O.O. Dengue virus and malaria concurrent infection among febrile subjects within Ilorin metropolis, Nigeria. J. Med. Virolo. 2017: 89(8): 1347–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24788

Дополнительные файлы